The Remarkable Evolution of TTI

Article By : Barbara Jorgensen

Paul Andrews Jr. did not set out to build a global distribution enterprise. “My first objective was survival”.

Paul Andrews Jr. did not set out to build a global distribution enterprise. “My first objective was survival,” he half-joked. “I’d been laid off from General Dynamics. I’d worked in manufacturing, procurement; I’d done inventory control, managed production, and had experience in sales. My primary goal was to make a living.”

In the early 1970s, Andrews founded Tex-Tronics — as TTI Inc. was called at the time — as a broker. Like distributors established in the 1940s, Tex-Tronics dealt with shortages, especially in military electronics. “There was always someone with a lot of low-value requirements on their desk,” said Andrews. “You just had to find that buyer.”

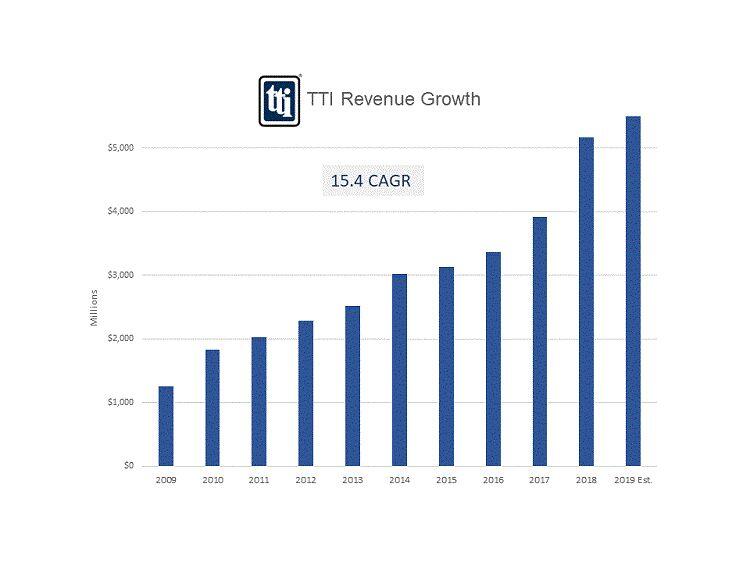

That was in 1971. Fast-forward to 2019, when TTI is a multibillion-dollar global distributor. The company remains true to its roots as a specialist, and its evolution is unique. TTI built its business on low-tech, low-cost interconnect, passive, and electromechanical (IP&E) devices. It never raised capital on a stock exchange. And it avoided the frenetic merger-and-acquisition activity that has shaped modern distribution.

The TTI way

TTI’s focus on IP&E devices started with Andrews’ interest in resistors. He knew that the OEMs around Tex-Tronics’ Fort Worth, Texas, headquarters — like General Dynamics, Collins Radio, Bell Helicopter, LTV, and Texas Instruments — weren’t good at managing low-tech parts. “I really felt there was an opening for a company that specialized in low-end components,” said Andrews.

He was right. IP&E products account for 80% of a typical printed-circuit board. It’s complex and costly to procure, process, stock, and sell vast amounts of “penny parts.” While other distributors focused on high-priced but volatile semiconductors, OEMs turned to TTI for their IP&E management.

Tex-Tronics received its first franchise, ACI, in 1973. It changed its name to TTI Inc. in 1974. By 1999 — well past the heyday of distribution consolidation — TTI was ready to buy a fellow specialist: catalog distributor Mouser Electronics.

Contrary to common practice, TTI never integrated Mouser into its business. Mouser sells semiconductors and other active components. Catalog and volume businesses have vastly different inventory, pricing, and logistics models. Mouser remains a standalone business within the TTI family.

“If you take Mouser and Digi-Key — the most successful catalog distributors — they have very high inventory and very low turns,” Andrews noted. “That’s opposite of traditional distributors. I spent a lot of time dealing with the military industry, and they don’t want a date code that’s a year old. So with this type of inventory, you have to turn your inventory constantly. At the same time, on commercial parts we carry a broad inventory with fewer turns than that of military.”

Catalog distributors stock every part they sell, but they don’t carry deep volumes of those devices. Fulfillment distributors typically stock for both breadth and depth. TTI, as a private company, has always managed inventory its own way. Publicly traded distributors often have to justify inventory investments to shareholders.

TTI was one of the first distributors to build its own IT system to manage inventory, Andrews said. “It was largely because of the low-value parts we sold. It was costly to process all those low-tech devices, so in 1987, we were one of the first distributors to computerize. Systems also enabled TTI to be one of the first distributors to offer a fully systemic Automated Inventory Replenishment Program to customers.”

Local, national, global

At the time of TTI’s founding, distributors housed inventory near their biggest customers. “In the old days — when dinosaurs roamed the earth — you had to have local inventory since transportation logistics was still emerging,” said Andrews. “We began branching out with no particular [geographic] strategy in mind. You opened a branch with someone who knew what they were doing.”

As TTI expanded, it duplicated its processes, inventory, and IT systems at every new site — an approach known as greenfielding. TTI’s aim was to offer consistent products and services at every site. “Not only did you need to deliver regionally, you received your franchises location by location, oftentimes state by state,” Andrews recalled. The electronics industry advanced rapidly during the 1980s. Local customers became national. FedEx and UPS revolutionized logistics. Distributors began to consolidate their inventory in hubs.

“Little by little, we began to centralize in Texas,” said Andrews. “Everybody said when we closed our local warehouses that we’d go out of business. Truth was, if we had maintained so many local warehouses we may have gone out of business.”

After nationalization, distribution went right to globalization. Arrow Electronics Inc. and Avnet Inc. led the charge, acquiring dozens of foreign competitors. “Global wasn’t something I really wanted to do,” said Andrews. “It was uncomfortable for me, but suppliers were requiring something beyond local distributors. In 1990, we expanded into Europe and in 2000 into Asia.

“If you look at the consolidation of distributors, it was led by people like Steve Kaufman at Arrow, whom I admire as a smart and intelligent person,” added Andrews. “That changed the industry, and Avnet was right there with them [Arrow]. That caused a large evolution in the industry — customer consolidation, supplier consolidation, and distributor consolidation. It was a major change.” It wasn’t until 2017 that TTI made its first major foreign acquisition: South Korean semiconductor specialist Changnam I.N.T. Ltd.

TTI gets acquired

TTI had a lot of suitors over the years. “I had acquisition opportunities that whole time,” said Andrews. “I had many conversations with large distributors. At the time, I didn’t feel the need to do that. I was comfortable doing what I did. Some acquisitions worked out well; other times, good companies fell apart.”

Paul Andrews Jr.

TTI has a solid reputation as an ethical, well-run distribution company. “As a large privately held company, you must always think about sustainability after the owner will no longer be part of the company,” said Andrews. “With no other family members in the business, I wanted to find a holding company that would allow TTI to continue operating as we had with great success.”

Upon visiting with Warren Buffett and finding that Berkshire Hathaway was interested, Andrews knew TTI had found the perfect parent. The US$247.5 billion holding company was known for hands-off management. Legendary CEO Buffett and Andrews developed a friendship beyond their business relationship.

“His philosophy is, ‘Just keep doing what you are doing,’” said Andrews. “We shook hands in 2006; we closed in 2007; and since then he hasn’t suggested we change anything. I assume that will continue as long as we are successful. If there was a significant downturn, that might change. It’s my job to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

Berkshire Hathaway provided a financial cushion if TTI wanted to expand further. TTI didn’t exactly go on a buying spree, but it acquired Sager Electronics in 2012, Symmetry Electronics and Changnam I.N.T. Ltd. in 2017, and both RFMW and Compona/Cosy in 2018. All are specialty distributors: Sager in IP&E; Symmetry, Changnam, and RFMW in active specialty and semiconductors; and Compona/Cosy in connectors. TTI continues to look for appropriate opportunities, Andrews said, as both Berkshire Hathaway and TTI are committed to profitable growth. “When you are managing a line card, you have to expand with your suppliers,” said Andrews. “We’re focusing on geography, which may tie into acquisitions. We prefer organic growth, so we look at what makes sense for us.”

Visibly, TTI has changed very little. Some back-end operations have consolidated, and “as part of Berkshire Hathaway we are more heavily audited than we used to be,” said Andrews. “There is a great deal of attention paid to compliance. That’s given us higher credibility with our suppliers, and we’re pretty sure we’re not going bankrupt. I’d say Berkshire Hathaway gives our suppliers a secure feeling, and the heads of those companies are not afraid to talk about future opportunities with us.”

Andrews never envisioned a global TTI that focuses on semiconductors. He credits his management team for the company’s success. “We were blessed with having a lot of good people dedicated to the vision of being a specialist,” he said. “We didn’t want to be the biggest; we wanted to be the best. I’m not an overly public person. We have better salespeople than me. People made the difference here.”

Andrews doesn’t assign a grand strategy to TTI’s success. “Our vision is, ‘Do it right.’ We are a block-and-tackle distributor. Maybe we’d be bigger if we focused on higher-technology parts, but nobody has ever won [a contract] by designing in a resistor. We sell the parts that populate the board after the semiconductor.

“We knew what we are good at, and we just kept working on it,” Andrews said.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss