Fixed Wireless Broadband is a Flop

Article By : Brian Santo

As of today, 5G is a solution in search of a problem, and that’s all it might be for a few years yet.

Verizon has said little about its introduction of 5G fixed wireless broadband service, so the good folks at MoffettNathanson Research traveled out to Sacramento to see what they could find for themselves. Their conclusions after a “laborious process” of evaluating Verizon’s first commercial 5G service are that Verizon installed minimal infrastructure, the cells it did deploy are disappointing in terms of coverage, and customer take-rates are miserably low.

Everything it saw in Sacramento could improve, but in MoffettNathanson’s final assessment, it believes it is going to be “challenging” for anyone to make money with 5G fixed wireless broadband (FWBB) for some time to come.

The report focuses entirely on Verizon’s commercial trial in just one market, but the report’s findings are discouraging for any company planning on rolling out 5G services any time soon, and disappointing for any wireless customers who let themselves be caught up in the industry’s relentless 5G hype the past few years.

The top line summary of MoffettNathanson’s report reads: “Our analysis suggests that costs will likely be much higher (that is, cell radii appear smaller) and penetration rates lower than initially expected. If those patterns are indicative of what’s to come in a broader rollout, it would mean a much higher cost per connected home, and therefore much lower returns on capital, than what might have been expected from Verizon’s advance billing.”

Pattern Recognition

The report allows that those patterns might not be indicative of what’s to come. For example, Verizon embarked on this rollout, installing equipment it knew was not standards-compliant. It placed that equipment in parts of Sacramento and three other cities (Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Houston), then announced it was holding off on further deployments until it could get standards-compliant gear. So, for example, the new stuff might work much better than what’s in place now. Verizon will eventually also deploy more infrastructure, will certainly start marketing more aggressively, and may very well attract a higher percentage of potential customers. The patterns can change.

According to MoffettNathanson’s evaluation, the patterns would have to change a lot. As of now, 5G fixed wireless broadband looks like a bad business.

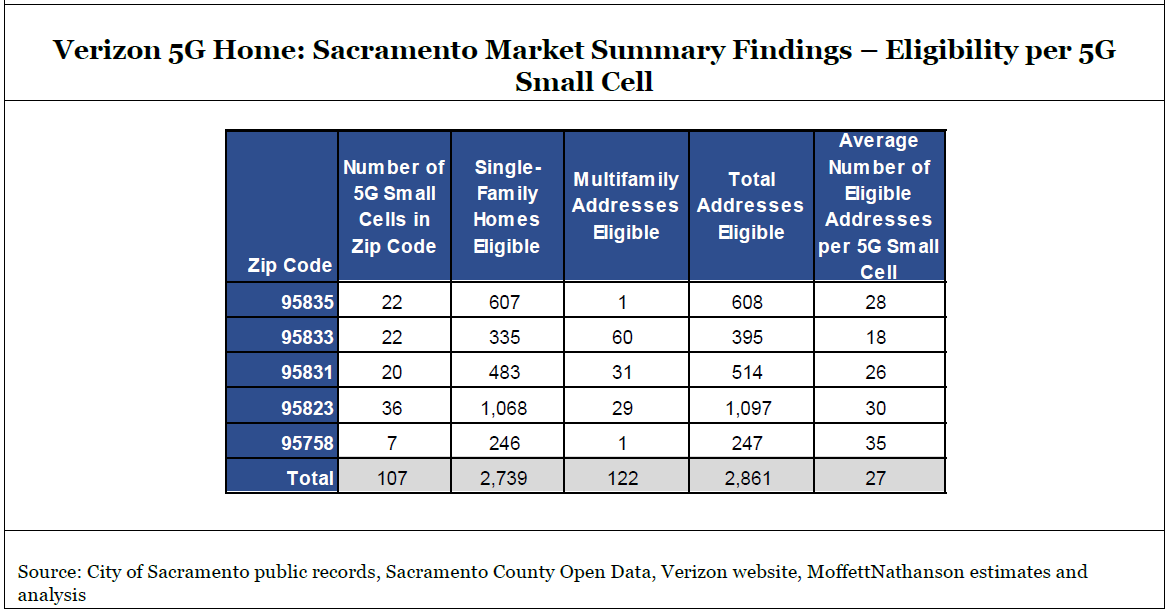

Verizon is being extremely conservative when it comes to determining whether it can offer fixed wireless broadband service to homes nominally in the radius of one of its cells. That said, the number of eligible homes per cell is very, very low. (Source: MoffettNathanson Research)

But that is news only inasmuch as the analysis confirms what A&T told the world almost a year ago: it is going to be hard to make money with 5G fixed wireless broadband.

During AT&T’s 2018 first quarter conference call with analysts in May of last year, AT&T CFO John Stephens said, “With regard to the fixed 5G wireless, if you will, our tests have shown it can be done. We can do it. The opportunity there is something that we have to prove out. We're not as excited about the business case. It's not as compelling yet for us as it may be for some.”

On the other hand, it’s possible that Verizon knows something AT&T doesn’t about 5G fixed wireless broadband, and that’s why it bulled ahead. But MoffettNathanson’s report belies that.

Patchy Coverage

Verizon’s coverage in Sacramento includes only patches of some neighborhoods. A separate analysis found that Verizon has covered less than 10% of the city, according to local reports. MoffettNathanson reports that Verizon considers only 6% of residential addresses as eligible, and fewer than 3% of those homes have subscribed, which MoffettNathanson notes translates into: “a market share of something like one tenth of one percent penetration.” It also translates into roughly 1.5 homes served per small cell deployed.

Take rates are a critical factor in calculating the economic viability of FWBB. The service is supposed to be cheaper than fiber-to-the-home (FTTH), a business that Verizon and AT&T have both tried, and which neither wants to invest much in anymore. But wireless broadband won’t be cheaper than FTTH if take rates are low; low adoption rates will mean the total cost per connected home will be high. According to MoffettNathanson, Verizon FWBB is currently far more expensive than FTTH.

Whether or not Verizon considers a home eligible for service depends first on whether or not there’s a small cell installed nearby. Then Verizon takes into account distance from the cell, possible obstructions (including foliage), and other factors. MoffettNathanson grants that Verizon is being very conservative with all of that.

MoffettNathanson also notes that right now, Verizon’s evaluations of eligibility for most potential subscribers require a visit by a technician. That constitutes a “truck-roll” in industry parlance. The costs of truck rolls add up real fast. Verizon vows that 5G fixed wireless broadband will someday be a self-install process. Easier said than done; there’s a whole sub-industry dedicated to reducing truck rolls.

Variable Cell Strength

This all leads up to what MoffettNathanson called its least splashy but most important finding: cells using millimeter wave spectrum aren’t limited just in terms of propagation and reach (compared to 4G cells), their radii are extremely variable because every cell is going to be situated in a unique local environment randomly filled with a variety of obstructions.

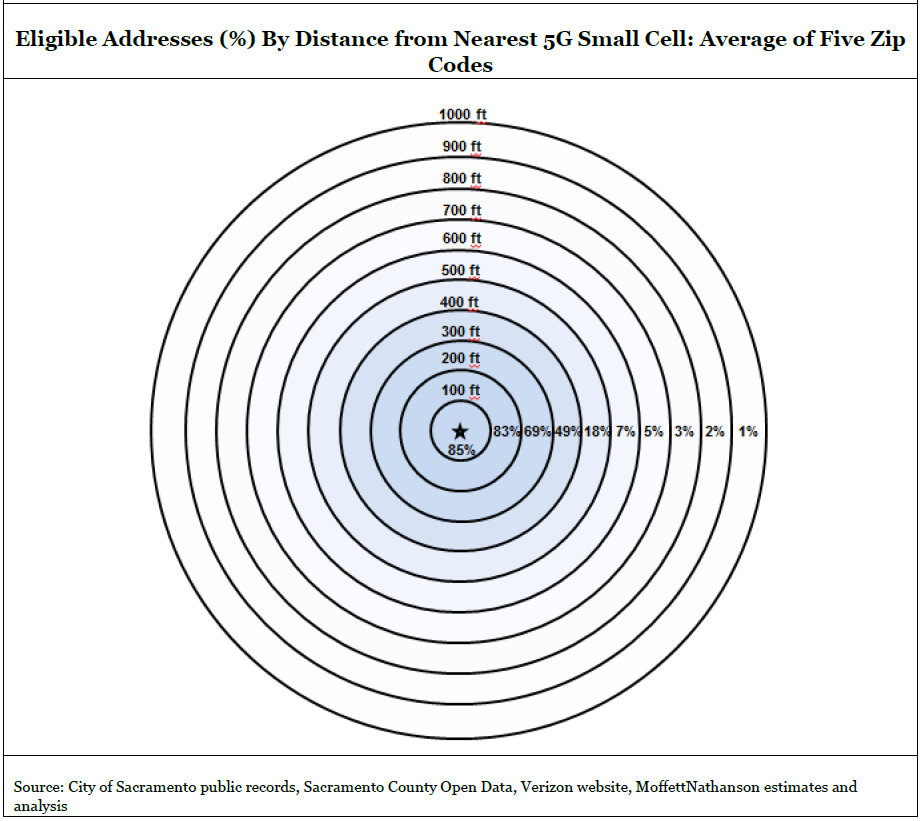

MN finds that as a practical matter, each cell tends to have an effective radius of about 700 feet. Compare that to Verizon’s boasts that its cells have an effective radius of 1,900 feet, MoffettNathanson noted. The analyst’s report states that with mmWave 5G, a carrier can’t evaluate eligibility, it can only factor in the probability of eligibility. There is no optimum spacing, and that’s going to make scaling the service difficult.

MoffettNathanson analysts calculate that one Verizon small cell covers only 27 eligible homes.

“It would be cheeky to suggest that, at 27 homes per cell, it would take something like 5.1 million small cells to bring FWBB to all of America,” MoffettNathanson cheekily wrote. “[O]r even that it would take 1.1 million to cover the 30M homes Verizon has indicated is their addressable market, but… well, the numbers are the numbers.”

The average reach of the small cells that Verizon is using is disappointing. This diagram suggests that beyond 300 feet roughly half the homes that should be reachable by the cell won't be eligible for service. (Source: MoffettNathanson Research)

Just about every technological condition MoffettNathanson found in Sacramento has been widely anticipated for years. Furthermore, more than a year go, AT&T did the math and figured out that FWBB was a bad business. It’s hard to believe Verizon didn’t or couldn’t make the same calculations as AT&T. So why would Verizon go ahead with a FWBB rollout?

The company promised to begin introducing 5G services in 2018 – as did AT&T. Both companies were hyping a global race to 5G that the United States just had to win. Their supposedly dire need to introduce 5G services in 2018 was why they browbeat the rest of the industry into accelerating the 5G standards process to finalize the 5G standards by 2018, instead of the original target date of 2020.

The rest of the industry knew long before 2018 rolled around that they wouldn’t be ready by 2018. That’s why they originally scheduled 5G standards ratification for 2020.

And sure enough, when 2018 arrived, despite the 5G standards having been rushed to ratification, there was no equipment ready. There was some hope that manufacturers could work morning, noon, and night and produce some 5G cells and mobile handsets by November or December of 2018, but that was an outside shot at best, everyone in the industry knew it, and of course it didn’t happen. Not only was 5G telephony off the table for 2018, it was never legitimately on the table. The only thing required to prove it was time.

Perhaps that’s just as well. What can 5G wireless phone service deliver that is so substantially better than 4G that the average user will pay for the difference? Nobody has a good answer for that. Downloading a movie really, really quickly 1 minute before your flight takes off instead of just merely quickly 15 minutes before your flight takes off does not seem like a profoundly compelling use case.

The AV/IoT Fizzle

But what about the commercial industrial/enterprise 5G services that are intrinsic to 5G standards?

These use cases tend to be placed in generalized categories – low-latency applications, or high-bandwidth applications, for example. That said, there were some specific applications that mapped to those categories that wireless carriers were whipping up excitement about. Providing connectivity for autonomous vehicles is a prominent example. Another is connecting together any number of innovative Internet of things … things.

But none of those use cases have materialized yet. The automotive industry is barely interested in using 5G, in large part because 5G coverage is so far from the required ubiquity that it isn’t even close to a practical option (except, perhaps, for the narrowest of applications). Most IoT applications make do with 4G, Wi-Fi, or some other existing connectivity option.

The bottom line is that if Verizon and AT&T wanted to deliver on their promises to provide 5G in 2018, if they wanted to justify the “global race” hype, they had few choices for actual services to roll out. AT&T chose to introduce wireless telephony based on what it called “5G Evolution” – something everyone else correctly identified as advanced 4G – and it got mocked heartily for it.

Literally the only potentially mass-market thing a wireless carrier could do in 2018 with 5G was what Verizon did – roll out FWBB – a service Verizon had to have known was going to be “challenging” because AT&T knew it. Unless Verizon wants to argue it isn’t as perceptive as AT&T?

The Neglected Question

All the focus on the nitty-gritty details about propagation of millimeter waves and the take rates on FWBB – those are the trees. What does the forest look like?

As of today, 5G is a solution in search of a problem, and that’s all it might be for a few years yet.

And since AT&T and Verizon knew this, it all begs a question: what was the hurry? Why did AT&T and Verizon push for early ratification of standards, even though the industry knew at the time that even with ratified standards in hand in 2018, the technology would not be ready?

Was it the global race to 5G? That makes little sense. AT&T and Verizon compete with US-based carriers, including T-Mobile, Sprint, and each other. There is no international competition, except perhaps for bragging rights. Who remembers who was first with 3G?

Perhaps Verizon and AT&T are claiming there's a global race among 5G equipment suppliers? Well, there is, but what’s that to AT&T and Verizon? What’s that to the US? There are few major, market-leading 5G equipment suppliers headquartered in the US.

And yet AT&T and Verizon are still beating that drum. The “global race” rhetoric is breathlessly passed along by FCC commissioners and the President of the United States, with no more rational explanation than AT&T or Verizon have provided.

Hurry Up and Wait

So again: why the rush?

Solely in terms of what has happened – disregarding anything written or said by Verizon or AT&T – as a practical matter – the only thing the rush has accomplished thus far is inducing Federal and state governments to impede cash-strapped municipalities from charging wireless carriers a fair price for their use of municipal assets. Specifically, the Federal government and some states have adopted measures that restrict the abilities of cities and towns to charge wireless carriers for the right to attach cells to municipal infrastructure – pole attachment fees.

This is no small thing. Wireless carriers are going to have to install many more 5G cells than 4G cells to get the same coverage. Estimates have ranged from four times as many to 30 times as many; MoffettNathanson in its recent report calculated it is likely to be at least seven times as many.

Whatever the actual number is, that number is roughly the factor by which the pole attachment fees that wireless companies are subject to would have increased.

In this photo from September, engineers from Verizon and Samsung test a pre-standards version of the latter's 5G small cell. The occasion was the achievement of 4Gbps throughputs using 28 GHz spectrum. (Source: Verizon)

AT&T and Verizon knew 5G was coming, and roughly when it would be coming, for more than 10 years; the 3GPP, which manages the global wireless industry standards process, has a very clear roadmap complete with dates. If that was somehow not enough, once AT&T and Verizon told the US they’d buy millimeter wave spectrum, they’ve known they’d be using millimeter wave spectrum. And of course they knew the propagation characteristics of millimeter waves, which means they had a very, very good idea a long, long time ago that they would need to install more 5G cells than 4G cells.

In other words, US wireless carriers had plenty of time to negotiate pole attachment fees with every municipality in which they do business. They’d already done it for 4G.

The only thing that was going to change was the cumulative price tag.

The Actual Bottom Line

So as a practical matter, based on everything that has actually happened to date, the rush job that Verizon and AT&T put on 5G has served one purpose, and one purpose only. It convinced the Federal government and some state governments to undermine municipal governments’ ability to charge fair fees.

The wireless industry has documented that many municipalities are attempting to charge unreasonable, perhaps even extortionate, pole attachment fees. Is that a legitimate excuse to undermine the ability of all municipalities to charge reasonable fees? And again, wireless companies have negotiated such fees in the past, and the cable industry has been doing it on an ongoing basis for half a century. It’s possible.

So Verizon and AT&T may not be making any return on their 5G investments yet, but they’ve successfully limited expenses.

MoffettNathanson provided a copy of its report, Fixed Wireless Broadband: A Peek Behind the Curtain of Verizon’s 5G Rollout,” to EE Times on the condition we not share the full report. It is available from the company.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss