Qualcomm Ruling Could Impact Industry Transition to 5G

Article By : Rick Merritt

The fate of Qualcomm’s patent licensing is in the hands of a U.S. District Court judge here. Her ruling also could impact hundreds of licensees the company holds across a cellular ecosystem in the early days of a transition to 5G.

SAN JOSE, Calif. — The fate of Qualcomm’s patent licensing — the most profitable business of one of the world’s top ten chip vendors — is in the hands of a U.S. District Court judge here. Her ruling also could impact hundreds of licensees the company holds across a cellular ecosystem in the early days of a transition to 5G.

Sadly, no ruling in the case of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm can change a broader reality the evidence shows. The tech industry’s way of determining the value of a company’s contribution to a fundamental standard is laborious, subjective and opaque.

The FTC argued Qualcomm charged for years unfairly high royalties for its CDMA and LTE patents while it held greater than 90% share in modems and used threats of halting chip shipments to win favorable deals. Qualcomm countered it repeatedly earned a position as a leader in a booming, dynamic market and sought fair value for its patents without ever stopping chip shipments.

In a 2017 ruling, the FTC persuaded a judge to order a drug company to pay a billion dollars in illegally gained profits. But in this case, the FTC is seeking an injunction to change Qualcomm’s licensing practices.

“The most likely remedy would be an order forcing Qualcomm to drop its ‘no license, no chips’ policy,” said Mark Lemley, a law professor at Stanford who focuses on the tech industry.

The judge also could force Qualcomm to license to rival chip makers, said Jennifer Rie, an antitrust litigation analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence. Currently, Qualcomm and other patent holders focus licensing efforts on system OEMs because it is the most lucrative and keeps negotiations simple, but the practice leaves chip rivals open to infringement suits.

In addition, the judge could forbid Qualcomm from insisting on cross-licenses as part of its deals. That was one flash point Apple objected to in its negotiations with the chip vendor.

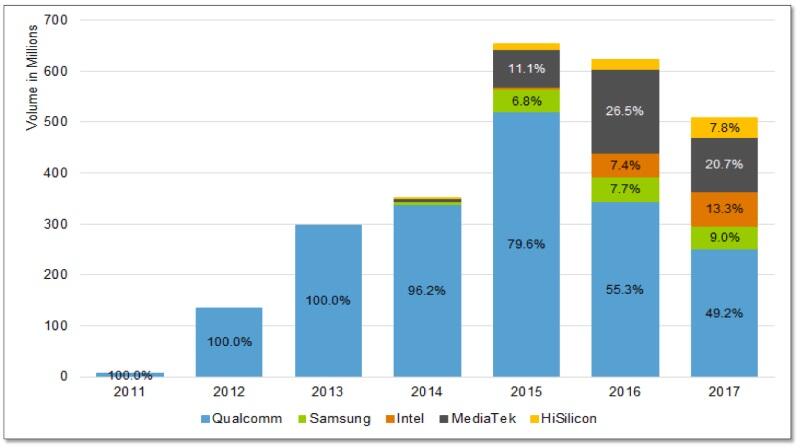

Although Qualcomm dominated LTE modems for a time, it’s share has dropped rapidly, said an expert testifying for the company. (Source: FTC v. Qualcomm)

Any decision against Qualcomm will reverberate through the company and the cellular industry, both at sensitive moments.

Qualcomm ranked seventh in global chip sales last year, but next to last in growth among the Top 50 at -3%, according to IC Insights. In the wake of losing its bid to merge to with NXP, its shed a billion dollars in costs. The cuts included an effort to expand into processors for cloud systems which are growing at a faster clip than maturing handsets.

Looking forward, Qualcomm is said to be 12-24 months ahead of rivals such as Huawei, Intel, Mediatek and Samsung in delivering 5G silicon. The initial 5G handsets shipping this year will be powered by its chips, and it already has struck as many as 50 5G patent licenses.

A decision will take at least until next week.

“There’s a tremendous amount of evidence to go through and the law is complex, so although I love to give speedy orders this will not be as speedy as my usual,” Judge Lucy Koh told attorneys shortly before testimony ended on Friday (Jan. 25).

Indeed, the record includes conflicting reports from top antitrust experts who took issue with each other’s reports, hours of depositions from dozens of OEM and chip executives, many detailed contracts, complete cellular specifications and volumes of emails to and from all the parties.

No such thing as a standards-essential company

An antitrust expert testifying for Qualcomm warned Judge Koh not to tamper with an industry that is shipping products improving at a rapid pace as net prices fall.

“Because the industry is thriving there is more of a downside risk of taking an industry rolling along by any indicator and throwing it into chaos and disrupting it — there’s a real downside risk with any intervention,” said Aviv Nevo, an economics professor and former chief economist for the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

An FTC attorney suggested Nevo was deaf to testimony from many handset OEMs. They complained Qualcomm’s royalties of up to 5% of a handset’s net selling price are well above rates from any other cellular patent holder. They also expressed frustrations over times when they lacked alternatives to Qualcomm’s chips.

Qualcomm helped pioneer digital cellular communications with CDMA and helped drive the shift from voice to data and multimedia co-founder Irwin Jacobs testified. Tinkering with its business model could stem the more than 20% of its revenues it pours back into cellular R&D, suggested James Thompson, the company’s long-time chief technologist.

“When I came to Qualcomm 27 years ago, I couldn’t afford a phone, and now half the population of the world owns a phone that’s also a computing device and a connection to the Internet…it’s something I am very proud to be part of,” Thompson said.

He oversees teams of more than 500 engineers, each working on areas such as cellphone cameras and mobile graphics. He recalled pressing his managers to staff up a 70-person multimedia team back in 2000. “At the time it was a big decision,” he said.

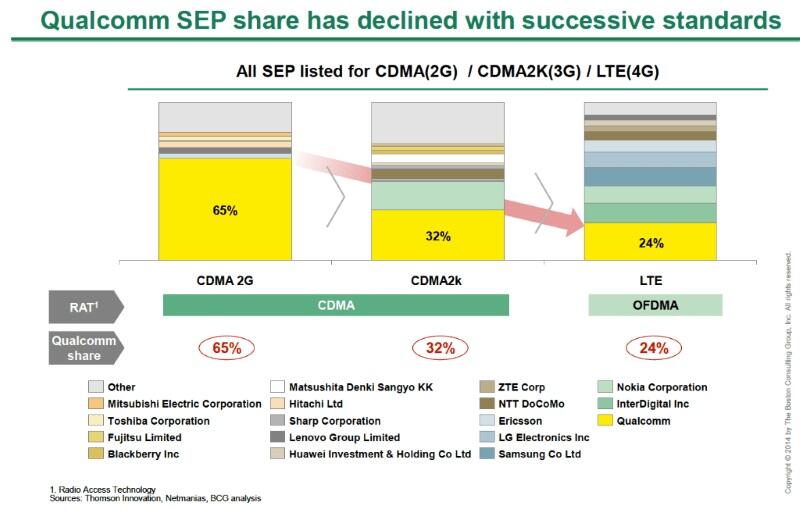

Qualcomm holds a declining share of the latest cellular standards-essential patents (SEPs). (Source: Boston Consulting Group for Qualcomm)

Qualcomm has to win its competitive position every year, Thompson said. He noted how in 2013 Apple came out with a 64-bit applications processor that left the chip vendor flat footed.

“Every one of our customers said, ‘you have to have a 64-bit processor core’…[so] very late in the game we had to swap [one] in…[but] we didn’t have time to optimize it, so it didn’t perform very well. Samsung…dropped us completely from its premium line and used its Exynos instead…it caused a lot of pain for us [because our chip ultimately] had a tenth the lifetime sales of other products,” he recalled.

Other experts said the cellular industry might grow faster — or at least more evenly — if its patents and profits were less concentrated in Qualcomm.

An FTC attorney alluded to an internal Qualcomm email from an engineering manager who oversees the company’s 90-person team at the 3GPP standards group. While the top five tech contributors could spin out a separate consortium from 3GPP and be successful, the next 10 could fill in the gaps and take over. “If the big boys leave 3GPP, there’s a line at the door to take their place,” the email said.

A patent’s value is what you can get for it

The complexity of the evidence mirrors the larger chaos of the market. Testimony sometimes gave glimpses into the sausage factories of creating standards and licensing patents.

For example, in one particularly long, complex negotiation, Sony’s lawyers arrived “very well prepared with a set of information about the applicability of their patents to our products —the thoroughness was more than I had seen before,” said Fabian Gonell, a vice president in Qualcomm’s licensing division.

“We provided equally detailed information about the level of applicability of our patents to their products — it was very expensive…and it took time.” It’s “fairly common” in private talks to provide such a detailed analysis of a handful of patents, Gonell said.

The problem is no one ever gets to the bottom of the bucket. Qualcomm alone has more than 140,000 patents and considers more than 20,000 of them essential to cellular standards.

So, when Apple suggested it enter arbitration with a goal of sorting through each of the companies’ cellular patents, Qualcomm sadly, but appropriately laughed it off as a non-starter.

“No human being could complete that task in a reasonable time…it simply wasn’t practical,” said Alex Rogers, president of Qualcomm’s licensing division.

Qualcomm itself has never tried to assign a value to its core cellular patents. Instead, the industry practice is to let the value come from whatever a company can get for a portfolio in licensing deals, said Gonell under cross-examination by an FTC attorney.

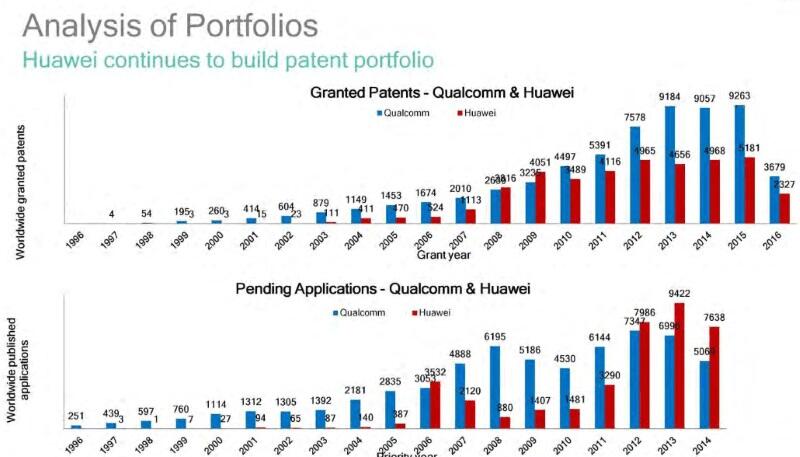

This 2016 document was from a Qualcomm report comparing its patent portfolio and 3GPP contributions to those of Huawei. (Source: Qualcomm)

The situation is equally murky when it comes to determining who made what valuable contributions to a key standard. “The 3GPP system was never set up to count anything,” said Lorenzo Casaccia, who heads Qualcomm’s 90-person team devoted to the group that has set every cellular standard since GSM.

Qualcomm and rivals count their contributions to the 3GPP process. Those contribution range widely from fundamental concepts that make it into the standard to minor big fixes and grammatical changes.

Companies have tried to game the system for years, Casaccia said, charging Ericsson and Huawei with giving engineers incentives for the number of contributions they make.

For example, sometimes engineers split a bug fix that could be submitted as a single document into as many as 20 separate contributions. Other times engineers ask if their name can be added to a list of sources of a contribution, so they can get credit with their employers, he added.

Frustrations have bubbled up at least twice in recent years at meetings of the IP rights committee at ETSI, Europe’s top cellular standards group. In separate letters to the group in 2011, Apple and Broadcom called for a clearer definition of FRAND.

“We discussed it for three years…there was no consensus to change the ETSI policy, said Dirk Weiler, head of standards at Nokia,. who led the ETSI IP group and now chairs the group’s overall board.

Squinting and basking in the court’s sunshine

At the heart of the Qualcomm case and many licensing issues is a lack of clarity.

Patents are valued by what companies can get for them in secret bilateral negotiations. No one knowns what anyone else pays. That can breed a toxic environment where everyone fears he is paying more than everyone else.

It takes a big licensor to push back hard enough that courts and regulators get involved. Apple’s falling out with Qualcomm was the spark for the current FTC case.

Likewise, Huawei’s push back led to regulators in China stepping in. Qualcomm’s Gonell recalled difficult negotiations with Huawei over two years, starting in 2013.

“Huawei said it was moving it’s [mobile] business to an unlicensed entity and it stopped paying royalties. After the negotiations were going on, the [China’s National Development and Reform Commission] NDRC investigation [of Qualcomm] started. Then Huawei took a harder negotiating position [offering less than a third of its initial proposal]. It quickly became clear Huawei was closely involved in the NDRC investigation,” Gonell said.

China’s NDRC action in early 2015 led to lower royalty rates for China’s OEMs that Qualcomm recently extended to any OEMs selling into China. Similarly, Korea’s regulators have reviewed Qualcomm’s deals with LG and Samsung.

The U.S. cases will include a trial starting this spring between Qualcomm and Apple. Meanwhile, Qualcomm is seeking injunctions against Apple for patent infringement in courts around the world.

Whether or not any of the cases force sustained changes in Qualcomm’s patent licensing, they are allmaking public details about who is paying what.

Some in the mobile industry may squint in the increasing sunshine while others bask in it. The San Jose case reveals the broader work of determining the value of a company’s contributions to a fundamental standard needs to get more transparent.

— Rick Merritt, Silicon Valley Bureau Chief, EE Times.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss