Who Should Define ‘AI Fairness’?

Article By : Ann R. Thryft

What different perspectives and disciplines, which stakeholders; need to be involved in determining the definition, or definitions if more than one are needed?

A question that often arises when discussing AI fairness is, who decides what fairness means? Can anyone agree on a definition, and on how developers can apply it to algorithms and models? One paper presented at the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Workshop on Software Fairness found 20 different definitions. What different perspectives and disciplines, which stakeholders, need to be involved in determining the definition, or definitions if more than one are needed?

Many organizations and research groups have published guidelines and best practices for delineating what AI fairness and ethics should be and how these should be implemented (see Guidelines links below). Beyond these suggestions, there are also some recent attempts at codifying guidelines and best practices into law. Several guidelines have been published by multi-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder groups, such as the Partnership on AI, which now has about 90 partners including both non-profits and companies, such as IBM. The most recent, and probably the most high-profile, is the European Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, released in April.

The EC guidelines reflect a consensus emerging during the last couple of years in the major concepts and concerns, in particular that AI should be trustworthy, and that AI fairness is part of that trustworthiness. As articulated by the EC, trustworthy AI has seven key requirements:

- Human agency and oversight

- Technical robustness and safety

- Privacy and date governance

- Transparency

- Diversity, non-discrimination and fairness

- Environmental and societal well-being

- Accountability

For IBM, four main areas, which comprise most of these seven, contribute to AI trust. They are 1) fairness, which includes detecting and mitigating bias in AI solutions; 2) robustness or reliability; 3) explainability, which is knowing how the AI system makes decisions so it's not a black box; and 4) lineage or traceability.

Francesca Rossi, AI ethics global leader at IBM, is one of the 52 members of the EC’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence that created its guidelines. She told EE Times a little about how the EC group arrived at its list. "We started from the European Charter of fundamental rights, then listed four main principles, and finally defined seven concrete requirements for trustworthy AI," she said. "Common in all these efforts, and to IBM's trust and transparency principles, is the idea that we need to build trust in AI and also in those who produce AI by adopting a transparency approach to development."

Rossi, who also co-authored the November 2018 AI4PEOPLE Ethical Framework for a Good AI Society, emphasized that each successive effort in writing guidelines builds on earlier ones. For example, the authors of the AI4PEOPLE initiative, whose paper contains several concrete recommendations for ethical AI, first looked at many guidelines and standards proposals. These included the 23 principles for AI from the 2017 Asilomar conference, the Montreal Declaration for Responsible AI, the IEEE standards proposals, the European Commission's earlier draft AI ethics guidelines, the Partnership on AI's tenets, and the AI code from the UK Parliament's House of Lords report. The authors grouped these together and came up with a synthesis of five principles for AI development and adoption.

Work to combine and merge these different efforts is ongoing, even if it doesn't result in the same principles for different kinds of AI or for different geographical and cultural regions. "It's important that this work of combining and merging is done in a multi-disciplinary way, with the collaboration of social scientists and civil society organizations — for example, the ACLU — that understand the impact of this technology on people and society, and the possible issues in deploying AI in a pervasive but not responsible way," she said.

IBM has created its own practical guide for designers and developers, https://www.ibm.com/watson/assets/duo/pdf/everydayethics.pdf. The guide helps developers avoid unintended bias and think about trusted AI issues at the very beginning of the design and development phases of an AI system. "This is fundamental because the desired properties of trusted AI cannot be added to a system once it's deployed," said Rossi.

Guidelines and Best Practices for Achieving AI Fairness

There are several proposals for guidelines, best practices, and standards for algorithms and the deployment of AI. Here’s a sampling.

- European Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI

- NEC Unveils “NEC Group AI and Human Rights Principles” The very short list of principles

- IEEE ‘s Ethically Aligned Design, First Edition

- Montreal (Canada) Declaration of Responsible AI

- AI4People’s Ethical Framework for a Good AI society: Opportunities, Risks, Principles, and Recommendations

- Everyday Ethics for Artificial Intelligence: A Practical Guide for Designers and Developers

- Translation: Excerpts from China’s ‘White Paper on Artificial Intelligence Standardization’

- The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence from The Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University

- A Harm Reduction Framework for Algorithmic Fairness

- UK Parliament’s House of Lords report on AI Includes an AI code with five principles

- Statement on Algorithmic Transparency and Accountability by the ACM US Public Policy Council and ACM Europe Policy Committee: Seven Principles

- The Asilomar 23 principles for AI development from the 2017 Asilomar conference

- Partnership on AI is established. Pillar 2 of 6 thematic pillars that will guide their work is Fair, Transparent, and Accountable AI

- The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, paper published in Cambridge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence, by Machine Intelligence Research Institute

Stanford Goes Multidisciplinary

A multi-disciplinary approach is part of the fundamental thinking underlying Stanford University's new Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, unveiled in March. The Institute's basic vision of a broader, more integrated discussion in creating AI and its positive potential is how its members see their research, by working with very diverse teams, said James Zou, assistant professor of biomedical data science and, by courtesy, of computer science and of electrical engineering. His colleagues include professors of history, economics, linguistics, education, law and business.

Whether guidelines should become policy, regulation and law is highly controversial, as is the level of granularity to be regulated, and who will decide the specifics. "There needs to be a lot more social engagement between the science and engineering community and the policy makers," said Zou. "We're seeing proposals and policies being made that sound reasonable at a high level, but which are extremely difficult to implement and deploy at the technical level. So there needs to be a lot more dialogue."

While much thought and work has gone into the production of the EC's AI guidelines, it's important to realize that the Commission states these are not intended to be used as new regulations or new law, said K.C. Halm, partner at law firm Davis Wright Tremaine. Halm is co-lead of the firm's AI Team, a cross-disciplinary team of attorneys advising clients on AI issues in media, consumer financial service, healthcare, regulatory and technology transactions. "These guidelines do articulate a process leading to a pilot project that will evaluate what parts can and can't be implemented, and what can be enhanced, dropped, or changed," he said. "What I think they anticipate is that organizations developing AI will adopt some of the components as internal policies, and will work closely with the EC to share ideas, provide feedback, and further refine these guidelines in principal."

The Challenge of Creating Ethical Guidelines

Developing a set of ethical guidelines around AI is very challenging because AI itself, its definition, and the range of technology systems and platforms it can be used on are very broad. "My takeaway is that the EC guidelines are intended to provide a framework for law or regulations," said Halm. "I anticipate the EC and other leaders in Europe will use a variety of different forums to talk about their guidelines and see who else is interested in adopting similar or different guidelines." This will likely be followed by work to identify those differences, and efforts around initial consensus building.

In March, the IEEE Ethics in Action initiative released the first edition of its Ethically Aligned Design guide, "intended to provide guidance for standards, regulations or legislation for the design, manufacture and use of AI/S [autonomous and artificial intelligent systems], as well as serve as a key reference for the work of policymakers, technologists and educators," according to a prepared statement.

With a large number of stakeholders closer to the technology than many of the stakeholders that developed the EC guidelines, the IEEE's guidelines may be a better place to start "for an AI company that wants to operationalize a framework for developing ethical AI," said Halm. The eight principles that the IEEE thinks values-based AI should be designed around reflect a significant amount of work in articulating concrete principles developers can use as a framework when developing AI systems.

These eight principles are:

- Human Rights

- Well-being

- Data Agency

- Effectiveness

- Transparency

- Accountability

- Awareness of Misuse

- Competence

If any of these various guidelines are adopted to some degree, their primary elements will likely be incorporated into ethical documents, governance documents, internal policies, and standards that guide how developers build AI systems, said Halm, "so there may not be a need for affirmative regulation or new law in this space." Meanwhile, the ACM has made a formal statement on algorithmic transparency and accountability, and the ISO/IEC began a working group on AI, both in 2017.

Regulations and Standards Governing AI Bias and Fairness

There are several proposals for regulations and standards to govern AI algorithmic fairness, as well as opinions by lawyers and heads of technology companies about law and regulations. Here’s a sampling.

- Democrats want feds to target the ‘black box’ of AI bias US senators propose ‘Algorithm Accountability Act’ that requires companies to “self-test” their AI systems for accuracy, fairness, and bias

- FDA releases white paper outlining potential regulatory framework for software as a medical device (SaMD) that uses AI or machine learning Although this framework is not about AI fairness it could set a precedent and may signal future FDA moves in that direction.

- Laws should monitor bias in AI, experts say

- Some Thoughts on Facial Recognition Legislation by Michael Punke, vice president, global public policy, Amazon Web Services

- Google Calls for “Flexible” Government Regulations on AI

- Perspectives on Issues in AI Governance white paper

- Microsoft: Here’s why we need AI facial-recognition laws right now

- Facial recognition: it’s time for actionby Brad Smith, president, Microsoft

- FTC Hearings Exploring Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, and Predictive Analytics Focus on Notions of Fairness, Transparency and Ethical Uses by K.C. Halm and others at Davis Wright Tremaine

- IEEE Launches Ethics Certification Program for Autonomous and Intelligent Systems Program will create specifications for certification and marking processes advancing transparency, accountability and reduction of algorithmic bias in Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (A/IS)

Concerns About Regulation

Concerns about attempts to regulate AI fairness and algorithms too closely or in great detail are several. They include exposing a company's intellectual property to public view, the burden that regulations and certification processes could place on developers and their companies, and the ever-present concerns about interpretation of fairness and bias. "Potential new regulations present special challenges of interpretation, scope and reach," said Halm. "So to try to develop a set of regulations that require AI to be totally transparent, or which permits persons to request that [certain] data from AI systems be deleted, presents real operational challenges for companies that would have to work under those types of rules." For smaller companies especially this could be a costly challenge.

Halm also pointed out that, although "there are many hardworking very intelligent, very thoughtful regulators, public policy officials, and federal agency directors, the number of people among them who understand AI technology is limited." That's why he thinks the right approach is "regulatory humility," characterized by FCC chairman Ajit Pai last November at an FCC forum on AI and machine learning. It's also the approach being taken by other federal agencies, such as the Federal Trade Commission and the Patent and Trademark Office. Those agencies are holding discussions and convening meetings with technologists, policy experts, industry and public interest groups to explore legal and policy issues in AI, he said. "So, to the credit of many of those regulators, they seem to be interested in building a record and trying to understand how the technology works, rather than moving immediately to try and adopt new regulations."

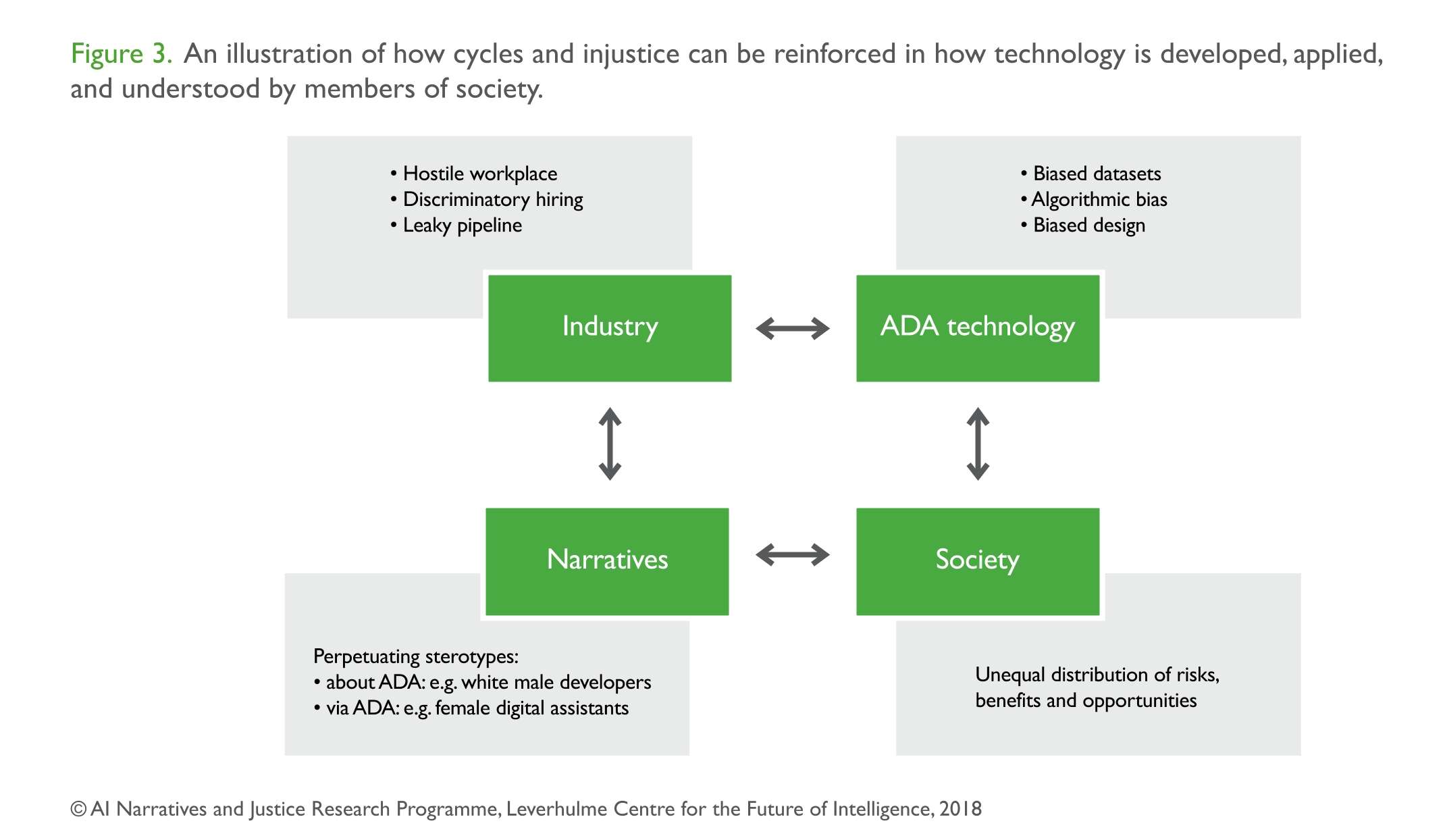

and understood by members of society. (Source: Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence)

But many do think that, to be effective, AI ethics and fairness must move beyond merely stating sets of principles and into standards, policy and/or regulations, so that biased datasets, algorithmic bias, and biased designs don't continue to reinforce societal stereotypes and unequal treatment. For example, a recent report from the UK's Nuffield Foundation and the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at the University of Cambridge describes a broad roadmap for work on the ethical and societal implications of algorithms, data and AI (ADA)-based technologies. It examines current research and policy literature, noting that these technologies impact nearly all questions of public policy.

The report finds that, while there's some agreement on issues, such as bias, and values, such as fairness, that an ethical approach should be based on, there's no consensus on what these central ethical concepts mean and how they apply to the use of data and AI in specific situations. There's also a lack of evidence for the current uses and impact of ADA-based technologies, their future capabilities, and the perspectives of different groups of people.

The report's roadmap identifies questions for research that need to be prioritized in order to inform and improve the standards, regulations and systems of oversight of ADA-based technologies. Without this, the report’s authors conclude, the multiple codes and principles for the ethical use of ADA-based technologies will have limited effect. The tasks for this research are: 1) uncovering and resolving the ambiguity inherent in commonly used terms, such as privacy, bias, and explainability; 2) identifying and resolving tensions between the ways technology may both threaten and support different values; and 3) building a more rigorous evidence base for discussion of ethical and societal issues.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss