Which Workstation Works for you? Do you care?

Article By : Kathleen Maher

Buyers are less clear about what kind of computing resources they need to get their jobs done, and workstation OEMs aren't helping much.

The definition of a workstation was once as crystal clear as the decision about having one. No longer. Our research has convinced us that people often don’t know what components are best suited to the job they are doing. As a result, people may opt for more CPU cores than they really need, and not enough memory. They might buy too much memory for the system and not enough on the GPU board (or vice versa).

They might not even be clear on what a workstation is. To be fair, the companies that make workstations aren’t being entirely clear about which of their machines qualify as workstations.

Rule one might be that if you don’t know whether you need a workstation or not, you probably don’t. The corollary to that is: if you do need a workstation, mistakes can be costly.

Once upon a time — a long time ago — if you needed a workstation, you knew who you were and you knew how to get it: ask IT. Alternatively: whine, bully, and demand it from IT. And the machine you got would have a RISC-based processor, a customized UNIX operating system, and would likely be a branded model and possibly customized for your job and applications.

That all gradually began to change with the advent of NT, the Windows-based OS for professionals, in 1998. Microsoft allied with Intel to destroy the specialized workstation market, and thus began the long confusing story of Windows workstations.

Blurring definitions

Then there’s Apple. Apple had its own processor, the PowerPC, which was also RISC-based; Apple also had its own workstation models. During the second tenure of Steve Jobs, Apple stopped branding machines as workstations, opting for the “Pro” designation. The company preferred to have a continuum for their products and not the hard split between workstation and PCs that has been typical of the Windows side of the fence.

So, why am I telling you all this? Because the sharp divide between workstations and PCs is also getting blurrier in the Windows world as well. PCs now include entry level machines that might even have Arm processors up through mainstream laptops, high powered gaming machines, portable workstations, and big honkin’ deskside workstations. Workstations are used for designing and building cars, airplanes, and convention centers, family homes; making movies, TV shows, special effects, and games; designing semiconductors; whatever job consumes computer cycles, onboard memory, hard drives, and the success of which is critical to the organization.

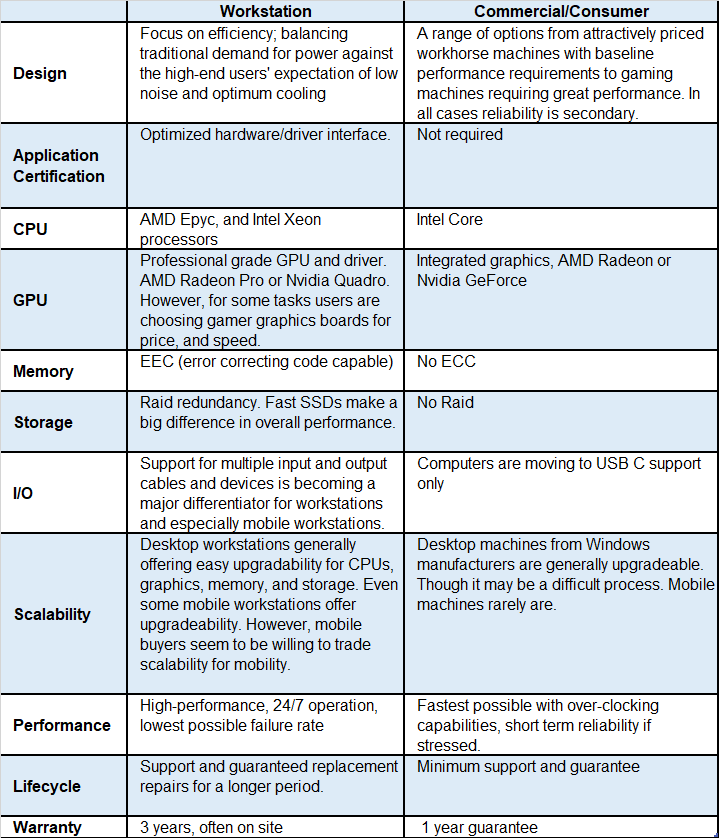

Workstations must have high performance, be reliable, dependable, manageable, and secure. In order to meet those requirements, the traditional definition of workstations includes these components:

Surprisingly, some people aren’t really sure what makes a workstation a workstation, and if they do know, they aren’t sure all those features are strictly necessary for their job. And, just as surprising, vendors aren’t helping make the lines any clearer.

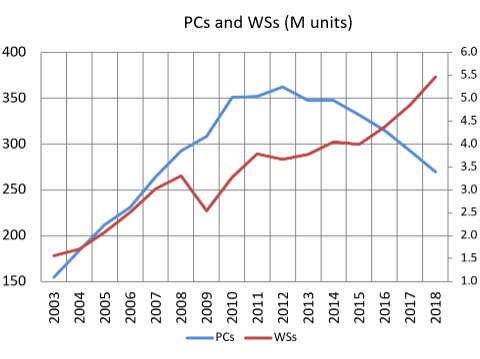

According to JPR’s Workstation reports, the workstation market segment has the highest margins for the total PC market. Compared to the PC market in general, the workstation market is pretty spectacular. It’s growing and it’s continuing to grow. For 2018, JPR analyst Alex Herrera reported that workstation sales increased 14.8% year over year. Compare that to the steady decline in the PC market over the years.

Herrera notes that the steady increase reflects economic optimism worldwide. In his Q4, 2018 report, Herrera says, “Capex budgets are robust, while demand for higher performance, which buyers expect to translate directly to higher productivity, has no foreseeable end.” The situation is changing in 2019 and optimism might not be quite so pronounced, but so far, the indicators are still positive.

As a result, the competition is fierce and what used to be a pretty solid definition for workstations has gotten considerably squishier.

Vendors, including HP, Boxx and others are branding as workstations machines that have regular CPUs, including Intel Core processors or AMD Ryzen processors. Xi Computers for example, are advertising CAD workstations with a variety of Intel Core processors and options for GeForce or Quadro graphics starting at $729. Titan has big box machines with multi-core i9s and Quadro graphics, and price tags starting at $3,700. To be sure, the processors used are very good, but they don’t support ECC or a large memory space. They also lack the same robust security protections as their workstation counterparts. Surprisingly, Intel and AMD have shown tolerance for the branding slippage.

Taking a new direction

Meanwhile in Taiwan this year, at Computex 2019, Nvidia introduced its specifications for RTX Studio laptops, which are being built by OEMs such as Acer, Asus, Dell, Gigabyte, HP, MSI, and Razer. These machines feature Core i7 H processors and above and Nvidia GeForce RTX graphics. Technically, they’re not workstations, but they will feature specialized drivers for creative apps.

Nvidia has introduced Studio Drivers, which are tailored to creative users who want stable machines and optimization, but who do not want to frequently upgrade their drivers. Nvidia’s Studio Drivers will have measured releases after they are tested with software from Adobe, Epic (Unreal Engine), Autodesk, Unity, and Blackmagic Design. In addition, Nvidia is offering creative software developers access to CUDA-X AI software to add new features and automate tasks for imaging such as color grading, upscaling, etc.

The situation is confusing over in the Mac world as well. The iMac Pro is a beastly machine starting at an 8-core Xeon W, and has a range of high-end Vega GPUs that ship with it. Whatever Apple wants to call it, it is a workstation. The proposition for the MacBook Pro is not so obvious. They’re very nice machines with Intel Core processors and can be configured with lots of memory. The AMD GPUs are professional grade Radeon Pros. These machines are designed for working professionals, they have a big presence in video editing suites, and are the machines of choice for professionals in the arts and for design.

The people buying these machines with high end components, whether they fit the classical definitions for workstations or not, are not compromising. They are buying what they consider to be the best machines for the work they do.

Customers know what they want

The kind of machines that people buy has a lot to do with what they intend to do with them. JPR has performed research on software applications and the preferences of the people using them.

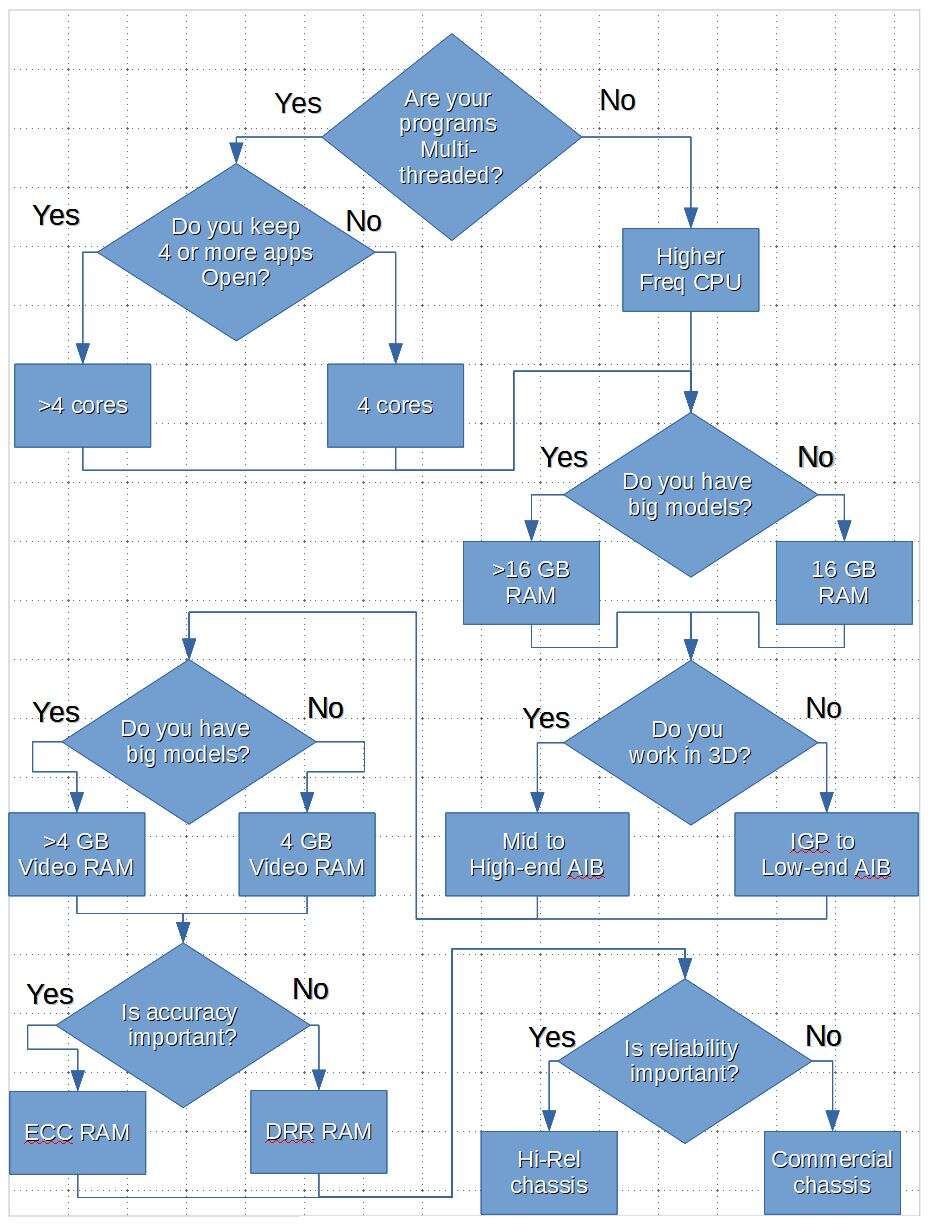

CAD applications place the most demands on compute resources. However, the trend towards multi-processing CPUs isn’t necessarily appropriate. The CAD programs in use today were developed in the 80s and 90s. They are not threaded and so it’s more important they have high speed CPUs rather than multiple cores.

In general, having 4-6 cores make sense for handling multi-tasking, and lots of RAM is useful to accommodate large models. When designing buildings, dams, or bridges, accuracy and fail-safe is important, so ECC should be a requirement. Dell takes that a step further with its Data Execution Prevention (DEP), which monitors one’s programs to make sure that they use system memory safely.

As for GPUs, the systems may benefit from the data parallelism of GPUs for visualization and analysis, depending on the applications used. In general CAD requires up-to-date drivers for reliability, but they don’t necessarily need the honkiest GPUs available, unless a lot of GPU-based rendering is required. The CAD programs themselves primarily depend on CPUs.

On the creative side, video and VFX are the showcase applications for workstations, but customers range from independent contractors and small studios to large film, video, and VFX houses. Programs like the Foundry’s Nuke or Autodesk Maya are also single-threaded and want speedy processors, but the pipelines include rendering, particle effects, color grading, and increasingly AI-fueled shortcuts, so lots of cores and powerful GPUs may make sense.

Who chooses?

We have also found that the choices made are also influenced by the size of the company and who is making choices. Workstations are bought by the palette for the automotive industry, large scale construction projects, the process and power industries, and by movie studios. In general, enterprise companies are not interested in saving a little money at the risk of equipment failure, security breaches, or numerical errors.

Small companies or individuals, on the other hand, are more likely to compromise. Small engineering and architectural house usually don’t have IT departments. The principals of the companies are the ones doing the work and buying equipment. They may feel comfortable about picking and choosing the components they want in their computers.

One of the areas where users have shown some willingness to compromise is in their choice of GPUs. Often enthusiast boards are more attractively priced than workstation class products — and they may win in benchmark comparisons.

We have seen engineers and developers in the game industry opting for gamer boards because it seems like a good idea to work on machines that are similar to those your customers are using.

Computers are getting very, very good, very reliable, and very fast. Many customers are probably right. They don’t need a workstation — as long as they understand the tradeoffs they are making.

And that’s where questions arise. Not all customers really understand the tradeoffs. In a recent survey study performed by JPR, we were surprised to find that many respondents felt that mainstream CPUs were fine for workstations, they didn’t understand the value of ECC memory, and assumed gamer boards were just as good as workstation class graphics boards.

We decided that the best way to help customers sort their way through the choices was to create a flow sheet. So far, here’s what we think it looks like for Windows users:

The definition of workstation has consistently changed. The bottom line is that it’s changing still. The key for workstation users is being aware of what it will take to get the job done, and then getting a workstation appropriate for the job.

– Kathleen Maher, vice president of Jon Peddie Research

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss