Patents and Standards Create Licensing Woes

Article By : Rick Merritt

Logjams have emerged for licensing standards-essential patents in codecs and cellular, but Wi-Fi may show the way

The latest codec for compressing video isn’t getting market traction because costs of licensing patents for it are unclear. That’s motivated a handful of efforts to fix decades-old problems licensing standards-essential patents that have dogged everything from cellular to Wi-Fi.

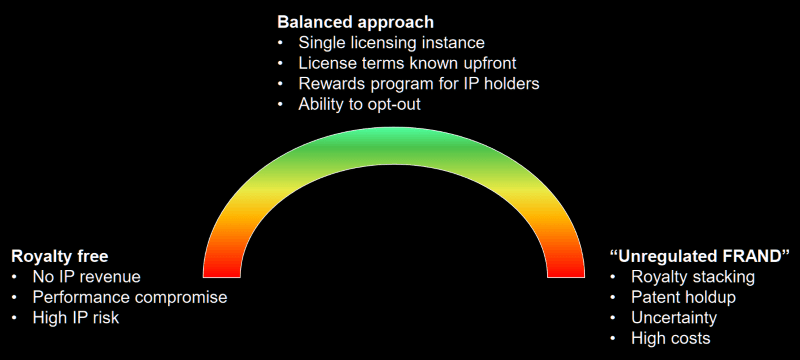

With some proposed standards, project members agree on licensing terms before work begins, rather than leaving the job to lawyers sometimes years after a standard is set. Others implement fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) licensing, an often-used concept that has proved to be dangerously vague.

Still others advocate a radical move to royalty-free standards. So far, this approach has not been immune from attacks from patent holders, nor has it been sufficiently motivating to attract some top technology developers, especially companies with significant licensing businesses.

There is yet no single method that guarantees a worthwhile return for developing new technologies while preventing abuse from opportunists and monopolies, given the industry’s diversity in business models, technologies and markets. And some see in standards-essential patents (SEPs) a Gordian knot that cannot be untied or cut.

“With the combination of the limited monopoly granted in a patent, and the de facto monopoly of a standard, the normal competitive forces that would determine a reasonable royalty don’t apply,” said Cliff Reader, an expert in intellectual property issues for video codecs who sees little hope any country will enact the kind of patent reforms needed.

“Patents and standards are the most challenging things to put together in tech,” agreed Karen Bartelson, former head of the IEEE who learned important lessons about SEPs in a patent “nightmare” over W-Fi.

Today, SEPs are key to the high-profile Apple/Qualcomm dispute over cellular, and they are starting to impact car makers, too. SEPs are the hot spot for H.265, aka HEVC, the codec central to many network operator’s plans to deliver ultra-high-definition content.

Patent wars in video codecs have raged off and on for years. It’s a field known for its deep base of constantly evolving technqiues critical for broadcasters, TVs and set-top makers and more recently video streaming services and smartphones.

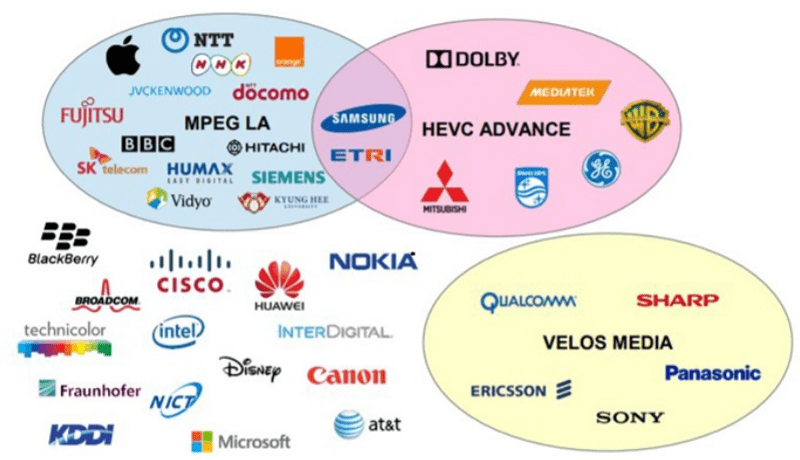

Tensions reached a peak when three patent pools emerged for HEVC. One of them, Velos Media, has not yet disclosed its licenesing terms, and more than a dozen large patent holders have not joined any of the pools.

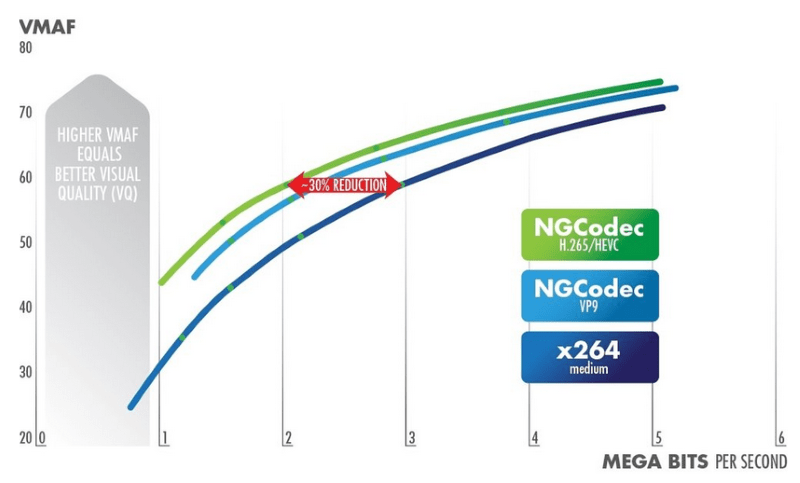

“That’s a complete nightmare to navigate, and it’s pretty disappointing because we founded our company in 2012 anticipating H.265 would become dominant,” said Oliver Gunasekara, chief executive of NGCodec, a video codec developer.

The uncertainty has kept the previous codec, H.264, dominant with an estimated 50% market share. The newer H.265 (HEVC) has less than 20% of the market, despite the fact it has been available for more than six years and is technically superior — it can cut bit-rates for H.264 in half without perceptible quality loss.

The core problem, Gunasekara said, is the MPEG group behind video codec standards focuses solely on technology, leaving others to sort out patent licensing terms.

“We can do 1,000:1 video compression live, and you can’t tell the difference — that’s mind blowing. MPEG creates video standards that matter, you can’t fault them technically, but they fall down by relying on FRAND,” he said.

The crisis got so bad that MPEG’s veteran leader, Leonardo Chiariglione, wrote a blog in January lamenting “the old MPEG business model is now broke.” He expressed fears royalty-free alternatives such as the AV1 standard started by Google will take over.

A royalty-free option still attracts patent assertions

In a defensive move, Chiariglione backed a royalty-free alternative at MPEG called the Internet Video Codec. But it failed when three countries informed MPEG’s parent group, the International Standards Organization (ISO), they have patents that read on it.

To date, AV1 seems the most likely of four efforts to break the logjam. It is already used by services such as YouTube and is backed by the Alliance for Open Media (AOM) with a dozen founders that include five top cloud providers and several major chip makers.

Samsung, active in most major codec standards, recently joined the effort. AV1 decode hardware is expected to emerge in chips in 2020.

“We are getting a lot of attention from China also, not everything is public, but it will be known soon,” said Debargha Mukherjee, a lead AV1 codec developer from Google. “We have a lot of big companies with big portfolios,” he said.

They will need them. AOM lacks several big codec patent holders including Ericsson, Nokia, Qualcomm and Japan’s consumer electronics giants.

Earlier this year, a new patent pool emerged asserting patents against AV1 and its forerunner VP9. Managed by Sisvel International S.A., a patent aggregator, its members include JVC Kenwood, Japan’s NTT, Philips, Orange and Toshiba. It claims its royalty rates are low, but they have no caps — and Sisvel put out a call for others to join the pool.

“The model promoted by the Alliance for Open Media is not suitable to all innovators that developed technologies needed to implement the VP9 and AV1 video codecs,” wrote Sisvel chief executive Mattia Fogliacco in an email exchange. “If companies hold patents necessary to implement the VP9 and/or AV1 technology, they have the right to see their innovation efforts and IP rights recognized,” he said.

AV1 proponents shrugged off the challenge.

“We follow a rigorous process, so that every tool used went through a patent review,” said Mukherjee of Google. “Some tools were taken out when lawyers told us there was a risk, but it turned out there were not many coding tools we had to take out,” he said.

The debut of a new pool “is normal in this early stage, but the AOM has a defense fund from member fees, and patents can be proven invalid with prior art or people can then pay them off,” said Gunasekara of NGCodec, which demoed earlier this year a software decoder for AV1 running on a Samsung Galaxy 10 handset.

“AV1 will be important. It’s a good alternative to the MPEG codecs and has a more predictable licensing framework,” he added.

Next-gen video codec seeks flexible patent position

HEVC’s problems have dragged on so long that the follow-on codec is almost finished and a new licensing effort for it is in the works. The Versatile Video Codec (VVC) should be finished in July 2020, offering about a 40% lower bit rate than HEVC and including new tools for high dynamic range videos and the 360-degree images needed for virtual reality.

As many as 300 engineers attended VVC meetings at their peak. Big contributors included Mediatek, Microsoft, Qualcomm and Samsung. China companies Alibaba, Bytedance, Huawei and Tencent also have been active.

Industry response to early VVC demos at a recent annual broadcasters’ event “was quite good… people were quite impressed, it was quite busy at the booth,” said Benjamin Bross, a researcher at the Fraunhofer institute who edits the VVC spec and also worked on HEVC.

In January, people from more than 70 companies attended the launch event of the Media Coding Industry Forum (MC-IF), a group that aims to ease the job of licensing VVC. Speakers included AT&T, Intel, Tencent, and representatives of the three HEVC patent pools.

MC-IF is still defining its goals that will likely take the form of suggested guidelines. “I don’t think we intend to structure licensing or create a patent pool; it will be more like an agreement for how a healthy ecosystem would function without mandating how to implement it,” said Jonatan Samuelsson, a board director of MC-IF and a former codec researcher at Ericsson.

Samuelsson also is chief executive of Divideon, a startup that has developed codecs that can flexibly add or remove tools — in part to defend against patent assertions. He explained his company’s techniques at the MC-IF’s first meeting.

Gunasekara of NGCodec was skeptical of VVC’s chances given it was developed under the same MPEG/ISO patent regime as HEVC. “If the licensing framework has not changed, we will have close to a 50% improvement — a huge technical achievement — but it won’t be adopted,” he said.

“I’m quite optimistic,” countered Samuelsson. “Without something like MC-IF we could just replicate the HEVC situation or it could be even worse with even more patent pools,” he said.

China rides in with dark-horse options

Two other alternatives to HEVC are interesting dark horses.

Samsung, Huawei and Qualcomm made a joint technical proposal early this year, later joined by Tencent and Divideon, to create a codec based on a set of legacy tools whose patents have expired. The so-called Essential Video Coding (EVC) effort is lobbying MPEG members to join, said Samuelsson who edits the emerging spec.

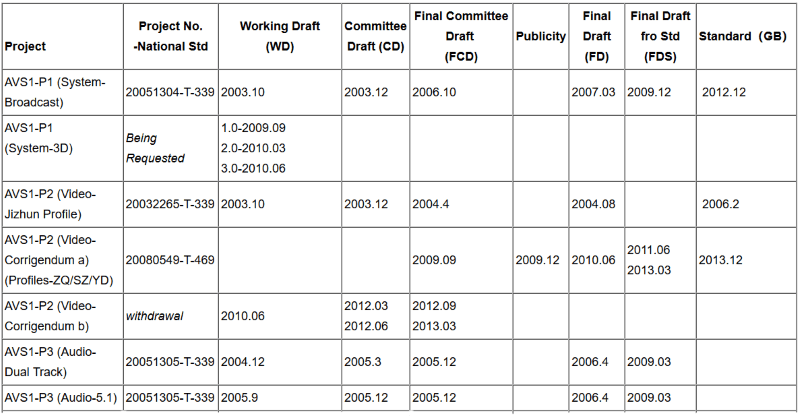

China was seeking an alternative to the MPEG process long before the HEVC woes. It formed the Audio and Video Coding Standard (AVS) group in 2002. It has already developed three generations of codecs that all started with an agreement on licensing.

AVS members must agree to license any related patents either royalty-free or at a relatively low rate, typically one renminbi per decoder unit and no charge to content users. “Some were not willing to sign up for such little money, so they withdrew,” said Cliff Reader, who helped write the legal agreements for AVS as the founding chair of its IPR committee.

At the time, AVS sounded like a clear and reasonable alternative to the MPEG-4 patent pool of the day. The MPEG pool wanted to collect both per-unit royalties from system implementations and per-minute user fees from content providers.

“The cost of complying and accounting for content royatlies was going to be horrendous and possibly ambiguous, leading to a possibility of fraud or suits,” said Reader, a PhD in video codecs who helped CableLabs set up a patent pool for MPEG-2.

By contrast, AVS got “commitments to licensing on known terms, and that’s more powerful than what the ISO or ITU can do,” he said referring to the International Telecommuication Union that oversees cellular and many other standards. “We have set an example,” he added.

Unfortunately, AVS has not gained a critical mass of users. It’s not used in streaming services or handsets. China mandates TVs support AVS+ which some satellite and cable-TV services licensed, but with relatively few channels, operators are not pressed for bandwidth, so they typically transcode content to MPEG-2.

Reader said the AVS-3 standard in the works has potenial for wider adoption. It targets performance similar to VVC with hopes for enabling 8K video at the Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022. “That may be the right time frame for infrastructure to move beyond MPEG-2,” said Reader.

A first cut of AVS3 is going through final review so the spec should be frozen soon. It should deliver about 22% lower bit rates than HEVC, said Lu Yu a researcher from Zhejiang University who was co-chair of the AVS video technology work group from 2005-2017.

She noted some satellite TV providers in Southeast Asia and South America use AVS+, and Tencent adapted AVS2 for the kernel of its Tiny Portable Graphics codec used to replace JPEG and other formats.

The codec patent battles could spread to AI some day. An AI working group in China is exploring use of AVS to compress neural networking models to speed machine learning jobs. MPEG has its own standards effort that was been working on the same opportunity for several months.

Despite the passion for AI among top cloud providers in AOM, Mukherjee of Google said there’s no plans to define compression techniques specific for neural net models in the AV2 standard in process. “The jury is still out whether that will be useful or not,” he said.

Patent lessons that Wi-Fi taught the IEEE

The IEEE standards group had its turn twirling in the patent blender a few years back. It emerged with a refined definition of FRAND it thinks others in sectors like cellular and video codecs could find useful.

Back in 2012, companies with no products to sell were asserting patents on its Wi-Fi stadards against end users. Both the U.S. Department of Justice and the European Commission were telling standards organizations they needed to revise their patent policies to address a growing backlog of court cases on standards-essential patents.

“Patent trolls were going into mom-and-pop cafes, claiming Wi-Fi patents — it was a nightmare,” said Karen Bartleson, former president of the sprawling IEEE organization.

“There was a huge discrepancy between what patent holders versus implementers thought patents were worth, so disputes wound up in the courts. There was fear competition would be harmed and people would stop setting standards or getting patents,” she said.

The IEEE spent nearly three years writing four drafts of a revised patent policy and combing through about 700 comments on them. The 400,000-member group that operates in 190 countries even got help from the likes of U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar (D., Minn.), now a presidential candidate.

The group aimed to create a policy that respected both patent holders and users, but “it was geo-thermal nuclear war…a lot of big companies with big money feared a big change,” Bartleson recalled.

Indeed, Qualcomm was so incensed it created a Web site attacking the revised policy issued in early 2015. It said in part, “these new rules will now undermine the incentives to invest in R&D and participate in IEEE standardization, which could drive engineering’s brightest minds elsewhere…IEEE’s ability to develop cutting edge standards will suffer.”

The new rules were basically clarifications of FRAND. They defined reasonable royalties as ones that are valued…

- …On the patent itself, not the value of the patent in the standard

- …On the smallest sellable unit implementing the patent

- …In light of all other claims that could be asserted to prevent patent stacking

The revised policy also said "non-discriminatory" meant rivals should be treated as equals. In addition, it also prohibited threats of injunctions and said demands for reciprocal licenses should generally be neutral to both parties

The IEEE asks for letters of assurance that members understand the policy, but mebers can ignore, negotiate or refuse to sign them. However, companies who participate in a standard but keep relevant patent holdings secret risk having the patents taken away in court.

Reactions and more thoughts on refining FRAND

Most sides expressed at least some dislike of the updated IEEE policy which suggests it is probably fair, Bartleson said. “In the past couple years, things have settled down a lot because of the update,” she said.

It’s too early to assess the full impact of the changes. Even the new 802.11ax standard (aka Wi-Fi 6), got its start before the effective date of the updated policy.

Despite Qualcomm’s warning, the number of new standards efforts at the IEEE continues to grow, according to internal numbers and a third-party study in 2017. Bartelson and others even think organizations developing video codecs, cellular, and other technologies could adapt the IEEE’s work.

Gunasekara of NGCodec has thought long and hard about FRAND licensing and has defined his own ideal attributes:

- Only patent implementers should be charged royalties, not end users.

- All essential patents in the standard should be part of just one pool that owners cannot opt out of.

- The pool should set a maximum for essential patents in the standard, ideally about $1/unit.

- Royalties should have total annual caps at about $100 million for a single company.

- There should be no royalties for companies selling fewer than 100,000 units/year.

- Codec royalties should be charged only on decoders, not encoders, and they should be agnostic to the resolution of the content and its target market.

“There is an investment in inventing these techniques and standards, so it’s not unreasonable companies get some return. The big probem is FRAND is very open to interpretation,” he said.

So, what should the cellular community do?

Like codecs, cellular has become a battleground for standards-essential patents. Over the past two years, regulators in China, Korea and the U.S. have weighed in on Qualcomm’s licensing practices.

Qualcomm charges as much as 5% royalties on smartphones, as much as $20/unit in some cases, more than any other licensor of cellular SEPs. The details only came to light when Apple, one of the world’s largest companies, took its concerns to court.

Under pressure to deliver 5G iPhones, Apple ultimately settled. But a decision in an antitrust case that could radically revamp Qualcomm’s patent licensing practices is still under appeal.

Related battles loom in connected cars where Wi-Fi and cellular proponents are battling over wireless standards. At stake is a lucrative pot of royalties many companies could pay for many years.

“Automakers are in a world they haven’t seen before,” said one IP lawyer at a top tech company who asked not to be named. “Car and car-parts makers are largely cross-licensed, but now suddenly they have to buy components with significant and unknown patent exposure and they are getting dragged into litgation,” he said.

The ETSI 3GPP group that oversees cellular standards will have to update its patent policies to bring clarity to cellular SEPs. But big patent holders such as Ericsson, Nokia, and Qualcomm are powerful members of the group, likely to resist such changes.

Today, the 3GPP keeps technology standards separate from any patent discussions. Indeed, in the antitrust case, the Qualcomm executive who leads its 90-person team at 3GPP testified there’s no way to trace what company contributed what specific concept to a cellular standard.

Nevertheless, “its quite common engineers make sure whatever is novel that they have developed will be patented by their company and brought to standardization. People are aware companies want to have their patents in standards,” said codec expert Samuelsson.

As cellular patent deals such as the latest one between Apple and Qualcomm expire, “there will be difficult negotiations and you will see continued disputes and litgation between handset makers and patent licnesing companies,” the IP lawyer predicted.

“We also see that new entrants into the cellular market, spearheaded by the automotive industry, produce a new wave of disputes between the inventors of cellular technologies and implementers,” said Mattia Fogliacco of Sisvel that maintains a 3/4G cellular patent pool and plans to add 5G patents to it.

TNO and Langbo, Dutch and Chinese R&D labs, respectively, recently joined Sisvel’s cellular patent pool. Separately, Sisvel has been acquiring cellular SEPs from Blackberry, LGE and others.

But even for Fogliacco who makes the area his business says, “the cellular SEP licensing market remains challenging.”

It’s challenging, in part, because the tech industry is largely split into companies that have significant patent licensing businesses and those who don’t. For many years the two groups have fought tooth and nail over royalty rates and who should pay them.

“I participated in a joint ISO/ITU patent process in mid-2000 in Geneva,” recalls Reader who later helped set codec licensing partices for China’s AVS group.

“There were people in the [Geneva] room from large corporations whose job title was licensing expert or standards expert. They were refusing then to agree to anything like what we are doing in AVS. They were from highly respected companies in all the major continents–not patent trolls,” he said.

The system needs to change, but it doesn’t want to.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss