Covid-19: We’re All in This Together

Article By : Junko Yoshida

Returning to the US from a month abroad, I was miffed when friends asked, “So that means you will self-quarantine for the next 14 days?”

I just spent a little over a month working in France, Spain and Scotland. I returned to the United States on Friday, March 13th, the last day that any “native” European was permitted to enter the United States — although US citizens and green card holders, who have constant contact with Europeans, are free to come and go.

Upon my return to the U.S., I was miffed when a couple of my friends asked, “So that means you will self-quarantine for the next 14 days?”

Seriously? However, I soon learned that this was the explicit recommendation of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Who knew?

I was away from my home country for just four weeks, but what a difference those four weeks made.

In late January, I was reporting on the spread of a new coronavirus that had triggered a lockdown not just in its epicenter of Wuhan, but in major cities throughout China that included Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing. Of course, at that time I was sitting in front of a computer in my cozy Madison home office, while gathering information from friends and colleagues back in China.

My friends in America were paying little heed to the emerging epidemic. Simply put, this was a “China bug” in the minds of many people in the United States.

Covid-19: Where technology meets social science

Fast forward to Friday the 13th. As surprised as I was being labeled as dangerous because I flew in from France, I’m equally shocked that the United States took eight whole weeks — after being warned about Covid-19 — before hitting the panic button.

But here’s the rub. More than anything else, I’m troubled that my federal government has done so little to build the infrastructure that could prevent the epidemic from spreading, or to provide support to a frightened populace by launching a massive national Covid-19 testing regime.

When I landed in Minneapolis from Paris, I found no systems — such as infrared thermal imaging — at the airport. Nobody scanned me or any of my fellow travelers on Delta Flight 43.

Infrared imaging screening, used properly, is a vital tool in detecting elevated body temperatures in high-risk groups. On Friday the 13th, climbing off Flight 43, I was part of a high-risk group. Of course, I understand that thermal scanners and handheld thermometers are no panacea. Infected people could slip through the system.

As with any technology, thermal scans produce false positives and negatives. The system measures skin temperature, not body temp, rendering it susceptible to potentially higher or lower surface temperatures. Core body heat is the key metric for fevers.

But an imperfect device shouldn’t justify doing nothing, nor should it warrant the sweeping statement that all thermal scanners are useless. The simple fact is that a faulty tool in human hands can prove surprisingly effective.

This is where technology meets social science. Judging and adjusting to false positives or negatives is entirely up to those who install, use and administer such sensing devices.

And there is a good reason for using thermal imaging scanners at airports. As noted in a Science magazine article:

… Still, researchers say, there can be benefits [of thermal imaging scanning]. Evaluating and quizzing passengers before they board planes — exit screening— may prevent some who are sick or were exposed to a virus from traveling. Entry screening, done on arrival at the destination airport, can be an opportunity to gather contact information that is useful if it turns out an infection did spread during a flight and to give travelers guidance on what to do if they become ill.

In other words, technologies are only as good as the social policies and infrastructure in which they operate.

In the case of Covid-19, thermal imaging scans alone probably aren’t very effective unless immigration services enact a secondary screening mechanism that includes public health interviews and questionnaires. For anyone deemed possibly infected, testing — including a clinical exam and laboratory confirmation — should be obligatory.

Technologies alone won’t solve a problem this big. They can even prove counterproductive if their advocates underestimate the limits of any given technology or fail to grasp their impact on society. As we employ technology, we must keep figuring out how best to use them in ways that are socially acceptable — or at least tolerable.

Where is Covid-19 big data?

The United States is not known for a lack of technologies. When it comes to big data, data science and connectivity, this is a nation where Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook have been world leaders in digital innovation for more than a decade.

But this dominance has faltered in the battle against Covid-19. In this pandemic, the United States is still playing catch-up. The government delayed policy decisions for weeks. It hesitated to appropriate funds.

The administration has yet to initiate public-private coordination to build a resilient digital infrastructure against the epidemic. Last week, the president claimed at a White House press conference that Alphabet, Google’s parent company, is working with the White House and private companies to create a website that will help Americans find screening tests for the Covid-19 virus.

But here’s the catch. Despite President Trump’s claim, it turns out that the Alphabet project is “in its early stages and will initially be offered to residents in and around San Francisco and Silicon Valley,” according to the company.

A beta test in Frisco is far less than the nationwide mobilization that was implied.

Recommended

Covid-19: The Success Story of Taiwan

The case of Taiwan

Consider, by contrast, Taiwan, a region close to mainland China — where the Covid-19 outbreak originated.

EE Times technology editor Maurizio Di Paolo Emilio recently reported:

Researchers and engineers in Taiwan acted quickly together to create a management system for coordinating health and travel data, which made it easier for doctors to immediately check the patient’s travel history. This has helped with more accurate diagnosis and treatment of patients and ensured that they receive adequate medical care.

The combination of all this allowed the state to send an SMS as a pass to be shown at the border as a declaration of good health. Those in high-risk areas were quarantined and tracked down via their mobile phones.

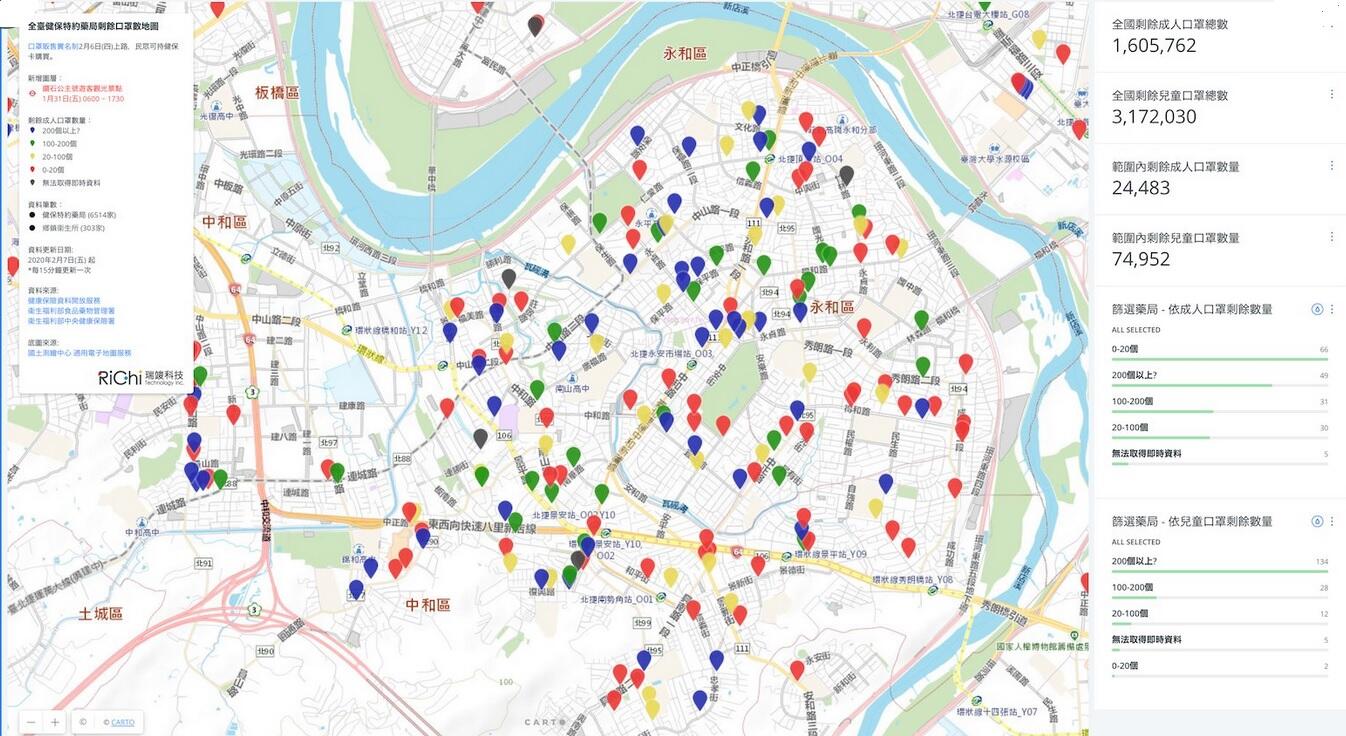

… [In Taiwan,] hoarding is not allowed, nor is there any need for it. The government has created an online map that shows exactly which pharmacy has the number of masks available, so you don’t have to queue or fight against other buyers to get a mask. This system for buying face masks was devised by Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s self-taught “hacktivist” minister of digital technology.

To be fair, it’s hard to imagine how the United States, a much bigger region that has thus far demonstrated little leadership and articulated few clear policies, could have replicated Taiwan’s anti-viral offensive.

Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s digital minister, shared a tantalizing taste of ‘social innovation by technology in Taiwan,” in an essay posted in medium.com.

Rather than choosing one political force over another in the face of an apolitical threat, Tang suggests that we ask a different set of questions: “What are our common values despite different positions?” And, “Given the common values, can we find solutions for everyone?”

In short, we’re all in this Petri dish together.

The U.S. tech community has made abundant advancements and innovations. It has accumulated knowledge and expertise in AI, data science and big data. Still, our technological edge appears almost helpless to solve the Covid-19 conundrum.

I believe we’re faltering because most of us are asking the wrong questions, and no one is even considering what minister Tang calls “social innovation by technology.”

After a brief overseas absence, I find myself very upset. Shame on the federal government for not swiftly and boldly devising policies to combat Covid-19. Shame on U.S. media who squandered several weeks by parroting politicians whose response to Covid-19 was to use it as a wedge issue against their rival partisans.

Most important, shame on big data platform companies such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook for their lack of imagination, their cramped aspirations, and for failures of “thought leadership,” which produced little innovation in public awareness that might have saved lives.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss