Blog: Are Telcos Ready for Openness?

Article By : John Walko

Not surprisingly, operators have latched onto the potential of a more open setup, both from the point of view of technology options and increasing competition in the infrastructure market.

The giant corporations supplying infrastructure equipment for the global mobile communications sector could be facing a seismic shift.

The underlying reasons mostly relate to the ever-increasingly important focus on software and artificial intelligence running the ever more sophisticated networks.

Virtualization of the radio access network (RAN) — arguably the most complex and costly part of the infrastructure — is gradually becoming a given. As such, it is causing significant technological and cost challenges to the three incumbent groups fighting it out for dominance in the market — Nokia, Ericsson, and Huawei.

The three are taking divergent views and differing approaches on how to meet the challenges posed by the Open RAN.

Meanwhile, the global and local operators are also having debates on how best to capitalize on the changes and the timescales involved.

In the current, traditional setup, the common public radio interface (CPRI) effectively mandates operators to buy dedicated, often proprietary, and thus costly equipment and systems from one of the big three. The lack of interoperability means that all of the access technology and radio units at one site need to come from the same vendor.

Not surprisingly, operators have latched onto the potential of a more open setup, both from the point of view of technology options and increasing competition in the infrastructure market. And the entire ecosystem is looking at and trialling multiple — and, in many cases, overlapping — initiatives to break the stranglehold of the triumvirate.

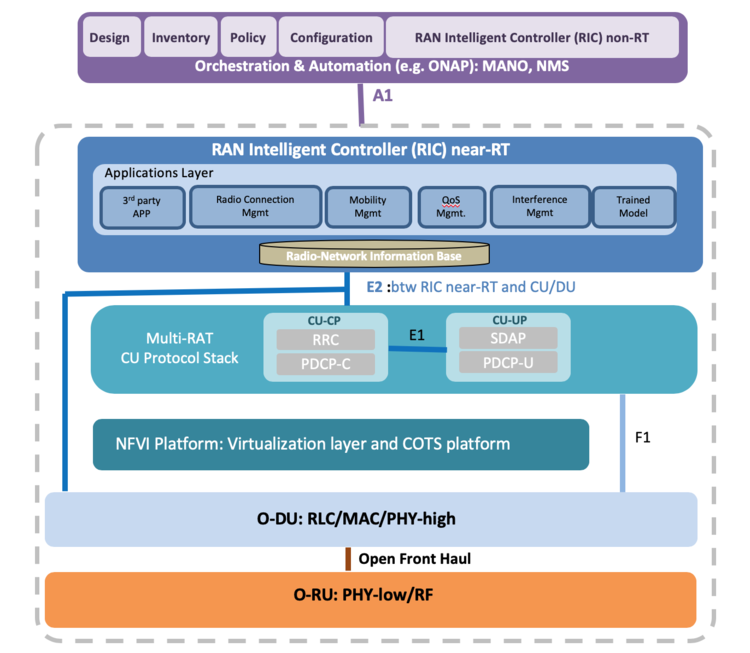

Motivations may differ amongst the operators, software developers, and equipment suppliers, but the target is universal — a disaggregated, software-driven, and, above all, open framework for the RAN — that will support existing flavors of mobile networks from 3G to 4G as well as the emerging 5G networks.

Perhaps it is important to stress at this stage that there is a distinction between an Open RAN and OpenRAN. The first refers in general terms to the move toward open interfaces and interoperability so as to build radio networks from potentially multiple vendor RAN sites and deploying commodity hardware units.

OpenRAN, instead, is the specific project within the Facebook-inspired and increasingly influential Telecom Infrastructure Project (TIP) that focuses on “developing a vendor-neutral hardware and software-defined technology based on open interfaces and community-developed standards.” So, unlike the traditional RAN, OpenRAN decouples hardware and software, offering operators additional flexibility as they deploy and upgrade their network architecture.

Also in the mix is the O-RAN Alliance, an operator-led group developing and certifying specifications for elements of an Open RAN such as RAN controllers.

Several startups and existing players in elements of the telecoms infrastructure business, notably in the U.S., see the situation as an opportunity to regain a significant foothold in a sector that was once dominated by the country’s technologists and equipment suppliers.

Of course, innovation at least never stopped amongst research groups such as Nokia Bell Labs and academic organizations such as NYU Wireless, but manufacturing by U.S.-owned companies has almost ceased, except of course at companies such as Cisco. The company has been very active with their switches and routers but, despite being urged to do so, has declined to get active in the access equipment sector, citing the costs of doing so.

And in a surprising initiative late last year, U.S. government officials are reported to have suggested offering credits to companies like Nokia and Ericsson in an attempt to counter Huawei’s dominance in the global infrastructure market. The Chinese behemoth has long been accused of offering extremely generous credit lines via the country’s state banks to operators so as to win major contracts.

U.S. government officials have said little about the initiative since its existence surfaced, but in any case, it would seem like shutting the door after the horse has bolted, not to say something of a contradiction of U.S. economic policy.

More likely is the possibility of the government steering large U.S. corporations to give a helping hand to home-grown innovative companies developing technologies for the Open RAN, such as Altiostar, Parallel Wireless, and Mavenir. For U.S. policymakers, this may seem the only viable way to take a stand in view of the huge logistic and economic barriers to entry into the vital network equipment sector.

Having said that, the U.S. seems pretty well-positioned in the race to deploy 5G networks, so one could argue: Where is the problem? All the big players have significant development activities and even some advanced manufacturing capabilities in the U.S. (save Huawei) — Nokia, after all, is a conglomerate that includes remnants of famous U.S. names in the infrastructure sector — Lucent Technologies and Motorola, to name but two.

On the operator’s side, it is European companies such as Vodafone and Telefonica, as well as NTT DoCoMo in Japan, who seem to be leading the charge. The former surprised the industry recently when it said that it planned to issue a tender to upgrade its entire European mobile cell-site footprint of some 120,000 base stations with Open RAN technology. The tender, arguably the biggest of its type to date, is open to both traditional suppliers and emerging companies with the relevant infrastructure gear and know-how, Vodafone stressed.

The operators are basically sending a “wake-up” call to the entire supplier community to embrace “open” — interfaces, architectures, software — the lot. Their motivation is clear: to bring more effective competition in the market and thus, hopefully, reduce costs. In a recent briefing, Parallel Wireless suggested that deploying commodity servers and open-source code would shrink telcos’ equipment bill significantly over the next few years compared with the likely savings on using traditional architectures.

It certainly seems like a brave call by Vodafone. Replacing so much installed equipment —including much that is just being brought online for its 5G push — represents a very significant expense and a big risk. After all, for all its promise, the Open RAN concept is still unproven in a large commercial setting.

The tender follows extensive field trials by Vodafone in the U.K. and Ireland — the former with Mavenir, the latter with Parallel Wireless.

So how are the incumbents responding to the challenge? It is more than likely that the likes of Ericsson, Nokia, and Samsung — maybe even Huawei — do have their own in-house strategies and developments, some perhaps even at an advanced stage. But of course, to date, they prefer not to talk much about them and certainly have no plans to commercialize any of the goodies developed. They are likely to focus on systems that allow networking software to work on general-purpose hardware. For instance, Ericsson has already gone public with a RAN-virtualization project in collaboration with Nvidia that the companies say is targeted at disaggregated software and hardware but does not actually open up anything.

The big supplier that has embraced the Open RAN bandwagon most readily and decided that it was better to participate in the groups driving the work rather than actively resist them has been Nokia. It is the only one of the three that has joined the TIP — though, by its own admission, has not participated very actively, nor does it speak too much about its participation. Tellingly, it is not leading any of the project groups targeting infrastructure developments.

And Nokia did join the O-RAN Alliance at an early stage.

But competitors Huawei and Ericsson are firmly on the outside of the TIP and more than ready to downplay the significance of open-source technologies in the RAN sector.

Ericsson has only recently joined the O-RAN Alliance, but there are few signs that it is participating in any of the serious work. It has committed to contribute to the very important area of devising interfaces between the RAN controller and the core network, notably for 5G networks. This — specifically how these can/will operate — is likely to emerge as one of the biggest sticking points as multivendor networks start emerging.

Indeed, Vodafone referenced that one of the main reasons for looking so seriously at open ecosystems is a lack of 5G progress in some of the important areas defined by the 3GPP standards organization — the so-called Options 4, 5, and 7. Option 5, for instance, would allow operators initially to offer core 5G services on their existing 4G networks. Its other motivation seems to be that none of the triumvirate has signalled any realistic moves toward open interfaces.

Samsung has also joined and is cooperating perhaps more actively, having developed products that are O-RAN–compliant now.

Meanwhile, Huawei remains totally aloof from open-source developments and unconvinced, arguing that off-the-shelf equipment just does not measure up in performance terms to its dedicated offerings.

The Chinese group does have a point, and there will inevitably be roadblocks along the way for the Open RAN concept. To date, there are few servers designed specifically to work with open interfaces, and the companies promoting the concept with greatest enthusiasm will need to convince the operators that they have the manufacturing skills to offer high-volume production on a short timescale — and then the means to test and integrate them in a timely fashion.

There is progress. For instance, when Vodafone recently issued a request for information regarding 5G NR software based on RAN technology, seven companies responded — Mavenir, Samsung, Parallel Wireless, Altran, Phluido, Radisys, and Altiostar. They were, on average, 60% compliant with the RFI requirements, with Samsung scoring the highest.

The 5G NR request was accompanied by a series of “must haves.” The companies’ software had to run on x86-based servers, be ready to open their interfaces, and support O-RAN specifications.

Note that none of the big three responded.

Some argue that because there will be many relatively small groups involved at an early stage, operators will need to rely on systems integrators. This is already happening, and the incumbents are quick to point out that this might lead to a situation in which a telco would merely substitute one form of lock-in for another. And certainly, the integrator will take his fair share, pushing up costs.

Other skeptics, perhaps rightly, point to the operating complexities involved in any Open RAN setup. One noted that while a single, albeit giant, vendor gives operators “one throat to choke,” the alternative can mean many more numbers to call when something goes wrong.

So clearly, there are massive challenges ahead for any mix-and-match operation involving multiple vendors. From a technical standpoint, there are the likely headaches about integration for an Open RAN, matching that with stability.

And the operators will need to be sure about the financial stability of the relatively smaller companies they are dealing with. As hinted above, this is where government agencies and large financial institutions may be able to play their part.

The history of the telecom infrastructure business is also one of partnerships between big and small players that often leads to cohabitation. If — much more likely when — an Open RAN approach begins to take off, history could easily repeat itself.

How quickly that might happen, and just how disruptive it could be, remains to be seen.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss