Apollo 11: Astronaut Mike Collins

Article By : George Leopold

A paean to the astronaut and Renaissance Man who drove the bus during the flight of Apollo 11.

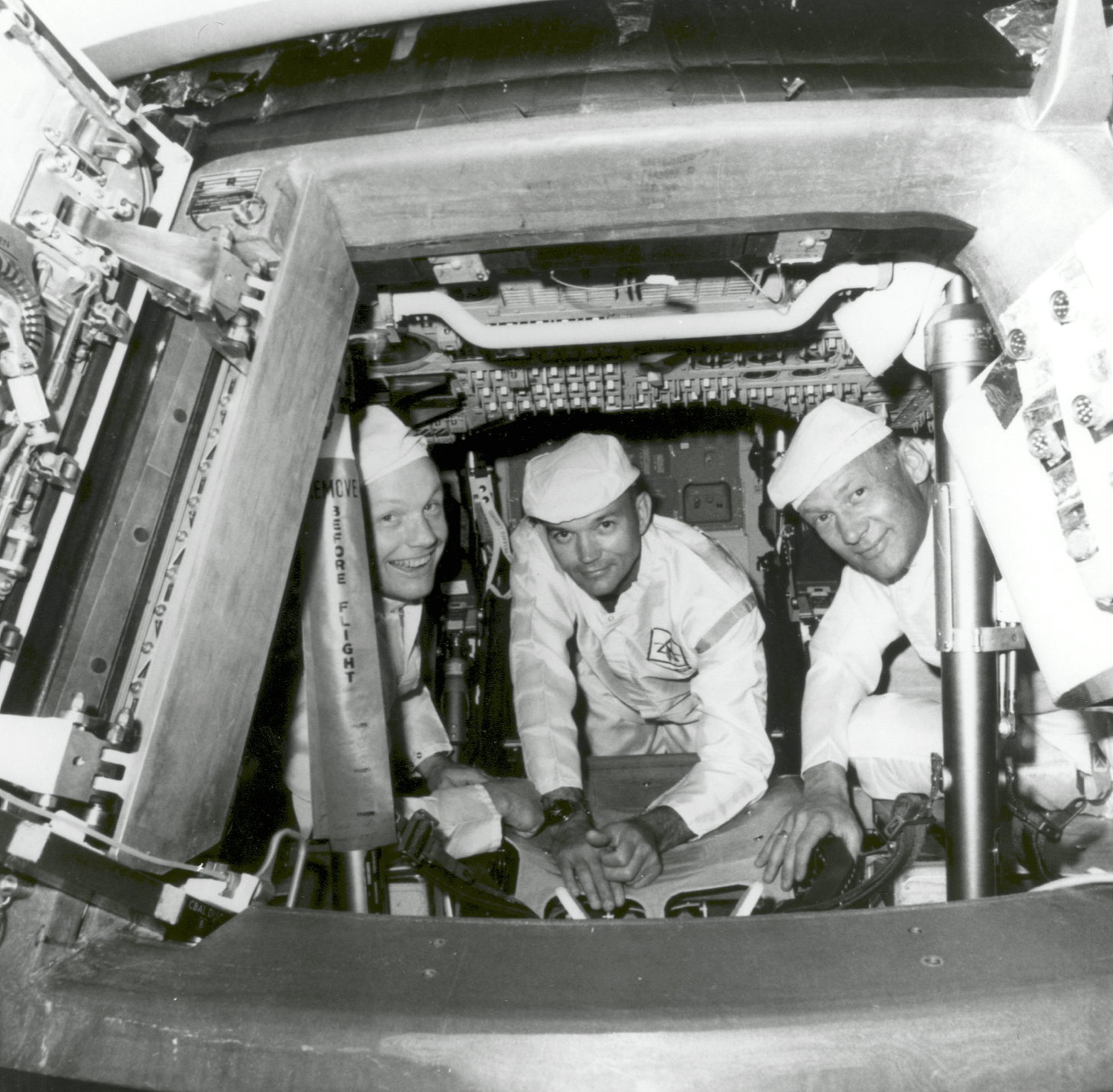

Apollo 11 checkout.

Introduced to a packed house recently at the National Press Club in Washington as “General Michael Collins,” the Apollo 11 command module pilot insisted: “No ‘General,' just Mike! ‘Old Mike’ if you want to be formal. And if you want to really get into it, ‘Lucky Old Mike.’”

The introductory exchange revealed much about a man who reached the pinnacle of his profession, all the while remaining humble, self-effacing, witty and, ultimately, wise.

Mike Collins was the one who remained behind in orbit while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made the first perilous descent to the lunar surface. Collins admitted he wasn’t sure he would see his crewmates again. It was his “secret terror.” He knew Neil Armstrong was the right man at the right time in history to land Eagle at Tranquility Base. What worried Collins the most was the single engine on the lunar lander’s ascent stage.

“We were great believers in redundancy,” Collins recalled. “We liked two or three of every little mechanical component.”

The nasty propellants in that ascent stage engine ignited on contact, which meant the single engine could not be test-fired before it was flown. It was a risk the astronauts had to accept. The engine had to fire. If it didn’t, “They were dead men,” Collins recalled. Thus, as he circled the moon alone for 21.5 hours, Collins prayed the ascent engine would light so he would not have to fly home alone.

The engine fired, of course, and when Collins saw his crewmates approaching above the mountains of the moon to re-dock with the command module Columbia, he marveled at the feat. It was as if Armstrong and Aldrin were riding on rails, Collins said. The moon walkers and their rocks made it back, and the crew of the first moon landing mission just as significantly became the first humans to return from the lunar surface.

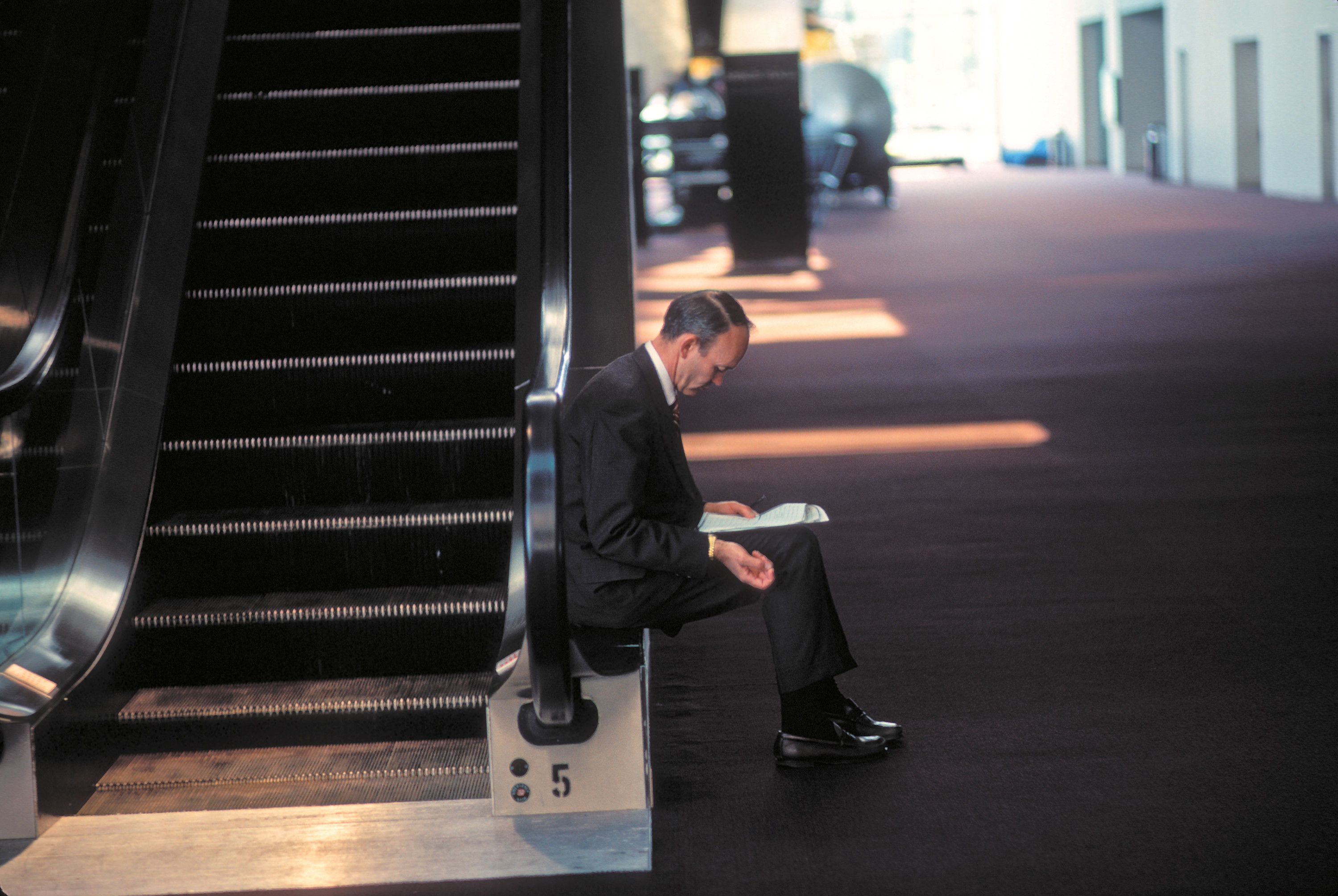

Collins in flight.

Mike Collins passed on his chance to walk on the moon, instead leaving the astronaut corps to add the word “Space” to what was then the Smithsonian National Air Museum. He also wrote the best astronaut memoir of the Space Race, along with two other books, all without the aid of a wordsmith.

Few would disagree that Mike Collins is the most erudite astronaut ever sent into orbit or to the moon. Pushing 90, he remains razor sharp.

Since Collins was speaking at the headquarters of the so-called “mainstream media,” he was asked his views on the subject of “Fake News.” The astronaut was at first reluctant to discuss politics, but the subject was bound to come up situated as he was a few blocks from the White House. Eventually warming to the topic, Collins delivered a full-throated defense of the First Amendment and the vital role of a free press in a constitutional republic.

Asked about President Trump’s attacks on the media, Collins left no doubt about his views.

Here he was, sitting in “the headquarters of the ‘enemy.’” Collins pointed to the crowd, asking the reporters: “Are you the enemy?”

“’Enemy of the people,’ my ass! The press is not our enemy. The press is our salvation!” (There was no need at the Press Club to cue the applause.)

Collins was as competitive as any of the astronauts, and wanted to beat the Soviets to the moon. While flying to moon he berated himself for using what he reckoned was too much gas during the “transposition and docking” maneuver that extracted the lunar lander from the Saturn V’s third stage.

Now he takes the long view of the meaning of Apollo. Ultimately, it was about leaving, he has said.

Prepping for a speech.

Someone asked Mike Collins a fair question: How does flying in space possibly help humanity and its understanding of the universe?

The test pilot, astronaut, space walker, writer, painter, fisherman and former museum director has pondered that question for half a century.

Recalling the scene 50 years ago on his way to the moon at a distance of roughly 113,371 nautical miles*, Collins replied: “Once upon a time I was flying in space somewhere and I looked down and said, ‘Hey, Houston, I’ve got the world in my window.’ If you take that idea and expand it, you can have the world in your window. You can consider the world in your window, what you think about that world, how you think it might be changed, what part you might play in changing that world in directions you think are important for your values.”

As for the future, Collins concludes: “I don’t want to live with a lid over my head.”

Amen!

The product of a distinguished military family, Collins is among the most approachable and likeable of the Apollo astronauts, never taking himself or his accomplishments too seriously. The hero stuff is “baloney,” he insists. The astronauts did the job they signed up for. If you need a hero, check out a hospital emergency room, he says.

Always, Collins understands he came along at just the right time in the history of aviation and space flight.

“Lucky Old Mike.”

Aside from the great good fortune of being born in 1930, the fact is Mike Collins made his own luck, impressed his bosses with his competence, his dedication, his wit. We were lucky to have Neil Armstrong at the controls of the first lunar landing. We were equally fortunate to have Command Module Pilot Michael Collins along to make the star sightings, the mid-course corrections and all the other navigation steps in that fragile daisy chain that brought the crew of Apollo 11 safely back to Mother Earth.

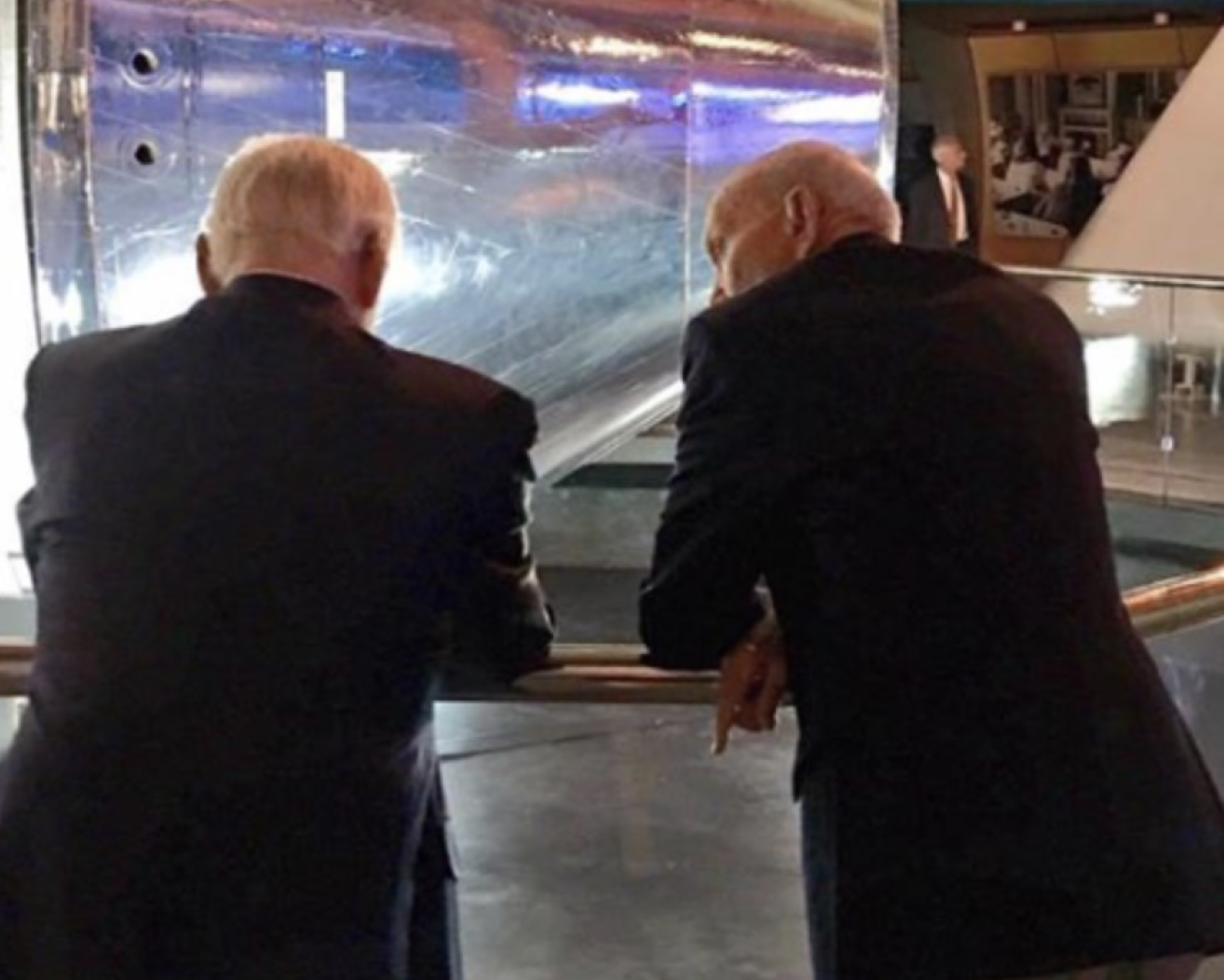

Aldrin (L) and Collins (R).

On their trip to the moon and back, Collins spent much of his time squinting through a sextant searching for stars by which to navigate. He would then punch those coordinates into one of the great inventions of Project Apollo, the command module’s guidance computer. When he wasn’t doing that, Collins was often working with ground controllers on roll and torque angles, midcourse adjustments and all the other steps required to send a space ship 240,000 miles and arrive at just the right spot in the solar system to enter a 60 nautical-mile-high lunar orbit.

Unlike his crewmate Buzz Aldrin, whom Collins informed Mission Control, “has his head out the window,” Collins was focusing on nouns (engine) and verbs (fire!) entered in the guidance computer. As his crewmates enjoyed the views of Earth and the moon, Collins reported, “All I’ve seen is the DSKY,” a reference to Apollo guidance computer’s display and keyboard.

When the crew of Apollo 11 fired its third stage engine to leave Earth and head for the moon, commander Neil Armstrong enthusiastically reported to Mission Control, “Houston, that Saturn [V] gave us a maaaag-nificent ride.”

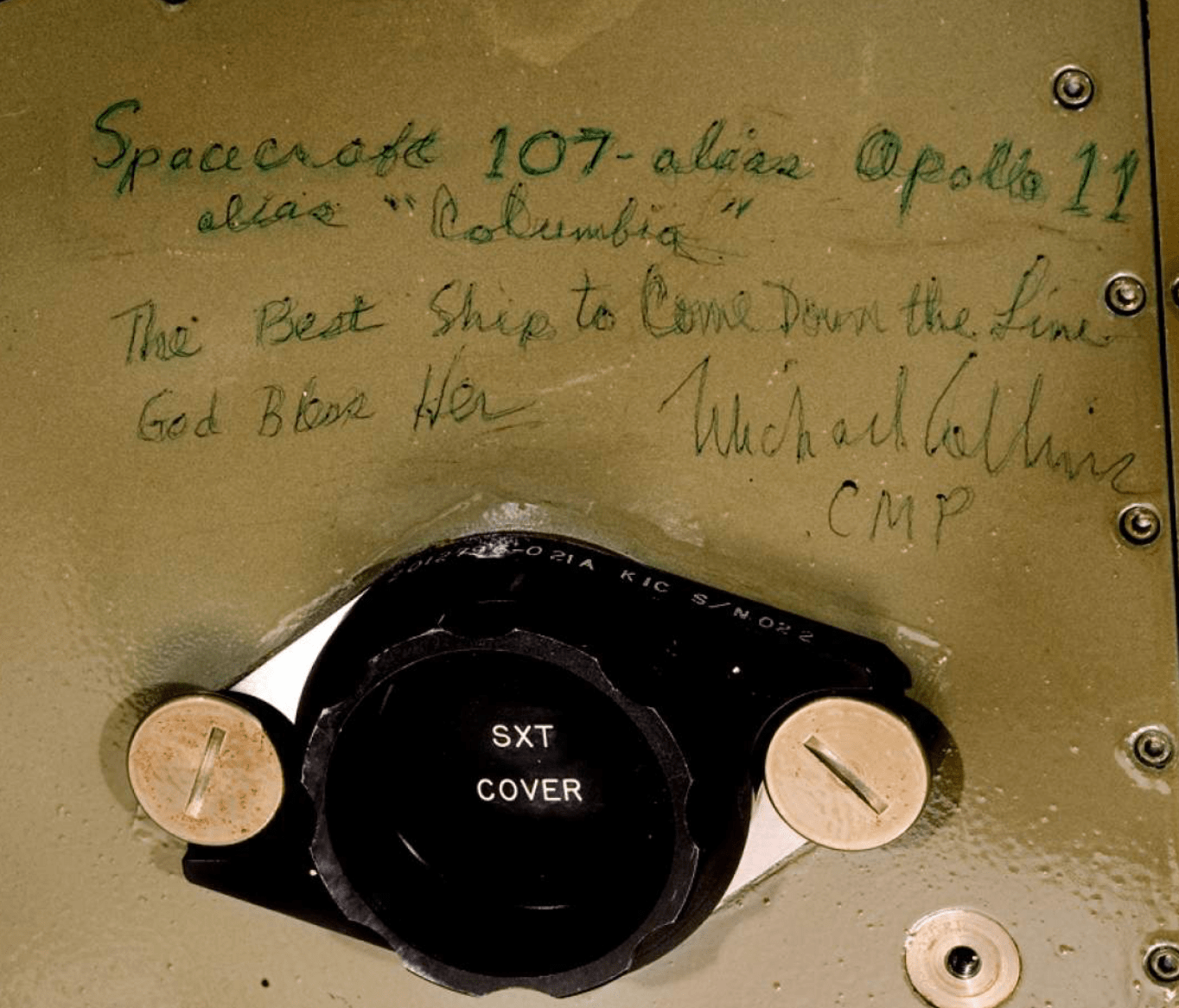

So, too, did Michael Collins, U.S. Air Force Major General, retired, command module pilot of the American Spacecraft 107.

It seems to us the Apollo 11 command module pilot appreciates what the nation spent to send him and his colleagues to the moon and back. It was a king’s ransom, arguably better spent on more earthly endeavors. It also appears that $180 billion in today’s dollars was worth the investment with explorers like Collins.

See more of Mike Collins' wit and wisdom here.

*The distance figure above comes from the excellent web site, Apollo 11 in Real Time, launched on June 15 by software developer and space flight data visualization researcher Ben Feist.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss