Qualcomm Defends Licensing in FTC Trial

Article By : Rick Merritt

The U.S. FTC questioned more than half a dozen patent-licensing incidents at Qualcomm as it closed its antitrust case. Co-founder Irwin Jacobs told his company’s story and defended its practices as Qualcomm opened its case.

SAN JOSE, Calif. — The U.S. Federal Trade Commission questioned more than half a dozen patent-licensing incidents at Qualcomm as it closed its antitrust case here. Co-founder Irwin Jacobs told his company’s story and defended its practices as Qualcomm opened its case.

An antitrust expert for the FTC cited Qualcomm’s “no license, no chips” policy, its refusal to license chip rivals, and its exclusivity deal with Apple.

“Qualcomm could use its chip leverage to get unreasonably high royalties on standards-essential patents, so when an OEM purchased a rival’s chip, it would be paying an unreasonable amount,” said Carl Shapiro, a Berkeley economics professor and former chief economist for the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Testimony spans CDMA, 3G, and LTE eras

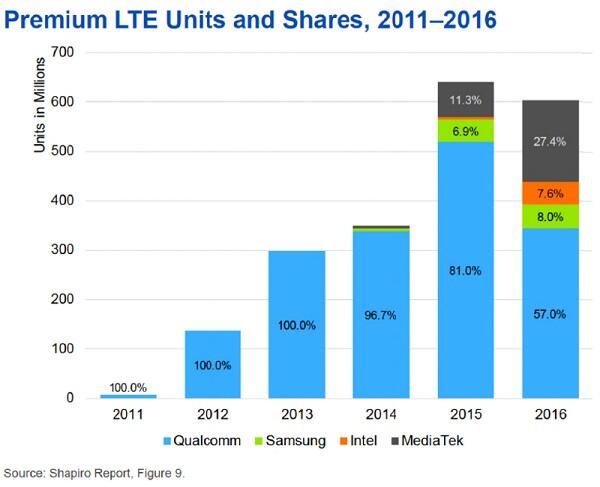

Shapiro used court testimony and market-share studies to conclude that Qualcomm used monopoly power on CDMA and LTE modem chips through 2016 in ways that harmed system makers, rivals, and consumers. A lead attorney for Qualcomm noted that Shapiro did not attempt to quantify any harms and that his study was theoretical in nature.

An FTC attorney showed Jacobs documents suggesting that Qualcomm reduced CDMA royalties for China Unicom in exchange for an agreement to use its chips worldwide. He also showed an email from Jacobs to a Samsung executive promising a royalty reduction if the South Korean giant continued to purchase a set percentage of its WCDMA chips from Qualcomm.

“They were a good customer, purchasing a large percentage of chips from us, and we wanted to encourage that,” said the 85-year-old Jacobs, who served as Qualcomm’s CEO until 2005 and retired from its board in 2012.

Qualcomm held monopoly power in both premium LTE and CDMA basebands through 2016, an expert for the FTC testified. Click to enlarge. (Source: Carl Shapiro)

In a 2004 letter, Qualcomm told an LG executive that it would have to stop purchase orders and shipments of WCDMA chips if the handset maker did not agree to pay royalties.

“This was for 500 and 6,000 [test] units, not production quantities … Chips for CDMA continued to ship [to them] during this dispute without any disruptions,” Jacobs said.

“They claimed if we shipped [the WCDMA chips], they would have no responsibility to pay royalties for those or other chips … I don’t know what the resolution was other than we continued to do business with LG,” he added.

A 2007 email from another executive noted that LG would pay a 5% handset royalty when using Qualcomm chips and a 5.7% royalty when using rival’s chips. During a separate 2001 dispute, Jacobs sent an email to a Samsung executive noting that Qualcomm did not ship chips to licensees not performing on their obligations.

“We had this dispute about whether CDMA 1x was included in an agreement, and without an agreement, we did not ship ASICs … The main issue was to remind him of that and to get this resolved,” Jacobs said.

Monica Yang, an IP attorney for Taiwan’s Pegtron, testified via video that the company was “under huge time pressure” in 2007 to strike a CDMA2000 license with Qualcomm to win business making Apple iPhones.

“When I negotiated, I knew you had to sign the [royalty agreement] to get the chipsets … We were in a position where we didn’t have much to bargain with,” Yang said.

Next page: Jacobs tells his story, Shapiro cites a caveat

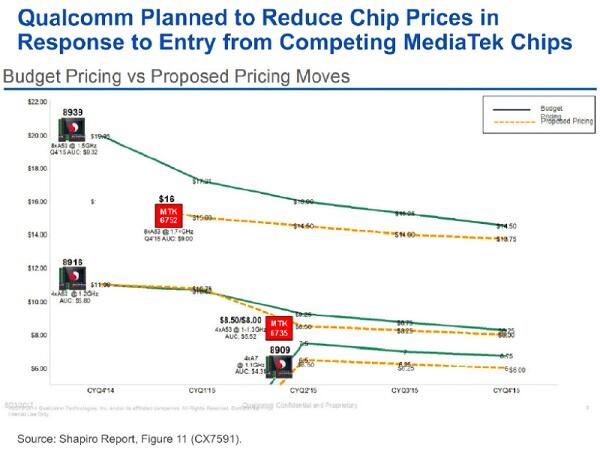

Qualcomm’s price reductions after the entrance of rival Mediatek in the market was evidence of a monopoly, one expert said. Click to enlarge. (Source: Carl Shapiro)

Founder tells his story, expert cites a caveat

Marvin Blecker, who retired in 2014 as vice president of licensing for Qualcomm, noted that the company sometimes offered incentives to get OEMs to adopt 3G rather than WiMax, an Intel-backed alternative. In an email to him, one Qualcomm colleague suggested cutting off chip supply to one customer involved in a protracted patent negotiation.

Under direct testimony, Jacobs said, “It was always our policy that we didn’t disrupt supply.”

As Qualcomm’s first witness, he also told the story of the company he co-founded in 1985 to explore opportunities in digital communications, a topic he co-wrote the first textbook on while teaching at MIT.

“At the time, cellular was based on analog — FM radio, basically,” he said. “People could see potential for substantial subscriber growth and a move to digital.”

Jacobs got ideas for how CDMA could be used while driving from L.A. to San Diego after a meeting with Hughes about a satellite contract. Qualcomm subsequently developed ways to use the then-unpopular technique to lower power, increase capacity, and ease handoffs in mobile networks.

One of its first CDMA demos that attracted interest was conducted in February 1990 from a van carrying a large prototype driving around Manhattan “in the middle of the night.”

To get the market started, Qualcomm developed three handset and two base station chips as well as its own handsets for the first networks in Hong Kong and South Korea. Back in 1995, “no one [else] had the confidence to build [CDMA] handsets,” Jacobs said.

The company also drafted text that formed the basis for a standard completed in July 1993. AT&T was the first to license the technology, followed by Motorola, providing funds to fuel the research.

Irwin Jacobs received a lifetime achievement award from Imec last summer. (Image: EE Times)

“It’s exciting to see something go from an idea to something used by people around the world,” he said. “I still get a kick out of going to a restaurant and watching people take their phones out.”

“Qualcomm should be commended for its technology achievements,” noted Shapiro in his testimony. “In a number of respects, they were leaders and had superior products — that’s one reason why they had market power.”

“What’s important is that companies who are not as good or don’t have scale are not impeded in challenging the leader,” he added. “If a company is ahead, it doesn’t mean they can trip up a company behind them — it means they can’t, actually.”

Judge Lucy Koh will rule on the case after Jan. 28, when attorneys for Qualcomm are expected to finish taking testimony. In April, a separate case between Apple and Qualcomm is set to begin proceedings in San Diego.

— Rick Merritt, Silicon Valley Bureau Chief, EE Times.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Test Qr code text s ss